“I’m actually feeling really lost with what I’m doing art wise,” he happily admits, “and there’s something invigorating about that.”

For all his professed uncertainty, Bates does not come across as someone who is feeling creatively lost, and the works in progress that adorn the walls of his workspace in Seattle’s Ballard neighborhood are testaments to his steady productivity.

Seeing Bates’ home studio is like opening a brand new pack of colored pencils: everything is satisfyingly uniform and perfectly laid out by color, and his drafting table seems too meticulously organized to be in actual use. But Bates in person is as precise as his paintings, and he keeps his studio organized to an extent that, like the photo shoot of a sparsely furnished modernist home, elicits a twinge of envy for a level of immaculate attention to detail that most of us will never be able to sustain.

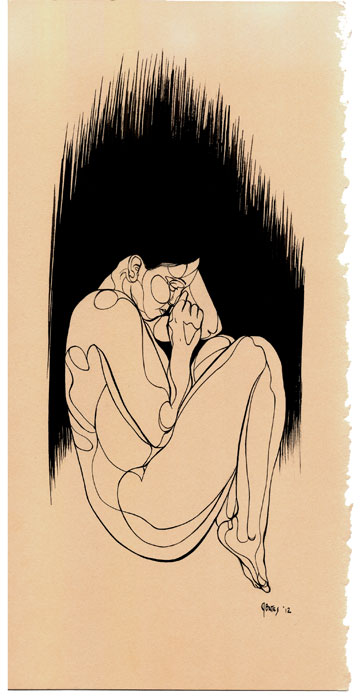

Bates works in graphite and gouache to segment the planes of the face and figure into a series of nestled curves, creating portraits that read almost as topographic maps. He reduces the arcs of the human form into shapes that draw the eye into a constant sense of movement, and the meticulous detail of his linework is so thoroughly exacted that it gives the deceptive impression of being effortless.

His first pieces concentrated almost entirely on faces, and by honing his focus in on the minutia of his models’ features, he shifted the emphasis away from his subjects as individuals and instead created psychological studies of specific expressions. Bates originally began observing the human face because of an interest in capturing variations in non-verbal communication, and his compositions are meditations on the myriad small parts that comprise the whole. His interest in expression arose from observing the ways that people communicate. “There’s something universal in expressions,” Bates tells me, “but there’s something very much not universal in how we read them, in the way we empathize and connect with each other.”

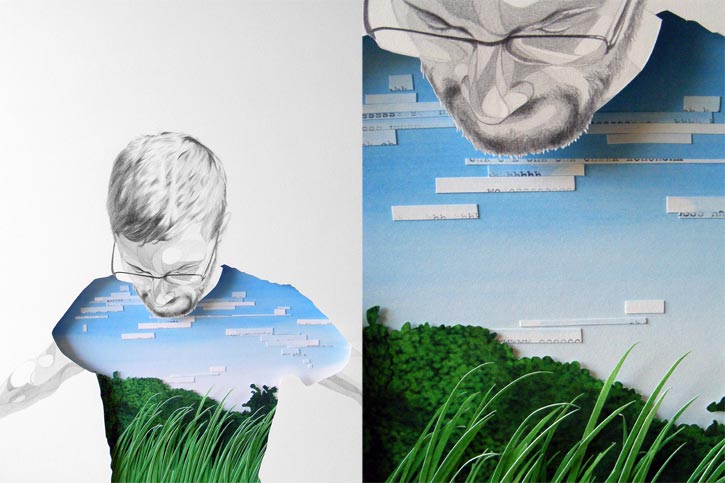

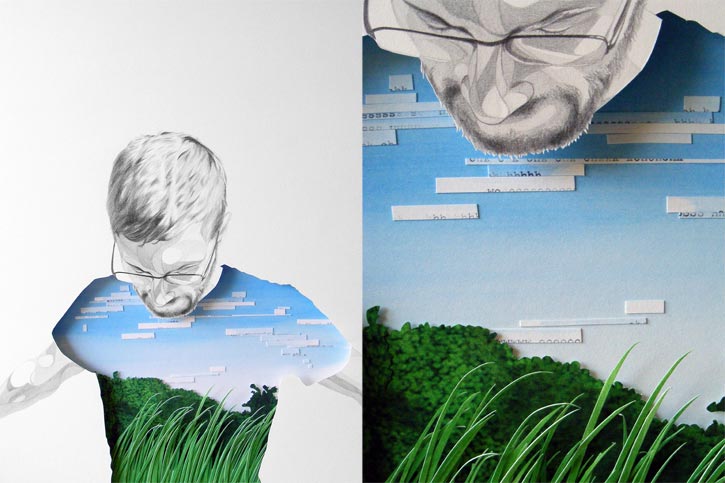

(L) Jillian, in collaboration with Shaun Kardinal; Helga, in collaboration with Amanda Fiebing

“I was having a bit of a rough year,” he tells me, going on to mention that viewers who didn’t know him personally seemed able to pick up on this from his work. “People would look at it and say, ‘There’s something wrong with him, there’s something going on.'”

Bates has taken this departure from portraiture even further and has recently begun painting mountains. Like his figures, Bates’ mountains focus on the detailed accumulation of sinuous folds and furrows, and he is more concerned with deconstructing the concept of a mountain than with representing any particular peak.

Viewed sequentially, these three distinct phases of Bates’ career reveal a clear developmental thread. His treatment of faces reduced expressions to their geometric components and his explosion series acknowledged that the face was never truly the emotional focus of his work. With his mountains, he is simply culling everything that furthers an underlying fascination with line and texture. Bates’ mountains seem like a natural progression — a concession that his work has always been about making portraits that are not necessarily about people.

Bates is an artist who holds himself to high standards, and he has never shied away from criticism. He isn’t afraid to be hard on himself, and he expresses frustration over what he sees as Seattle’s hesitation to engage in actual critique. There’s a fine line between expressing support for one’s peers and creating a comfortable bubble of self-congratulation, and Bates is not afraid to speak up when he feels like people have become too polite to criticize.

“I’ll admit,” he tells me unapologetically, “I’ve been that asshole who is at a show and says, ‘This is shit.’ And I’ll say it out loud to whomever I’m with, and the artist will be right next to me. And then I’ll say, ‘Well, here’s why it’s not working.’ As long as you can back yourself up, I think you should be able to say what you think.”

Bloom, gouache on black paper, 20″ x 30″

Explanation should be used to augment work, not justify it, Bates explains, and many of his pieces contain hidden nuances that only come up in conversation. In his piece Wind, Bates tells me that the seemingly random snippets of letters hanging in the sky of the painting are, in fact, the sound of wind transcribed phonetically on a typewriter. And the amorphous bushes? Those are patches of TV static caused by wind, printed out and covered in a green wash.

“The artist shouldn’t have to be there,” he emphasizes, though he also concedes that his own insistence on a strong technical base colors the way he looks at art, and that he has yet to find a way to be engaged by art that is more heavily weighted towards theory than practice. He doesn’t discount the possibility of there being a proper context for work that is predominantly concept-driven, but his own criteria demands a high level of technical competence.

“It’s hard when people are trying to do a concept but don’t have the facilities to execute it properly,” he tells me. “A lot of times [the work] falls flat because the foundation’s just not there.”

Bates believe that everyone can find value in the act of making things and that creative practice doesn’t need to be limited solely to people who call themselves artists, but he still struggles to find a balance between accessibility and quality.

“I always try to make my [non-artist] friends draw,” he adds, “and they end up really enjoying it.” Bates then pauses and laughingly adds, “I think everyone should make things. But I don’t think everyone should show things.”

His professional goals involve securing gallery representation, and he plans to spend the next year working on expanding the reach of his art outside of Seattle. As much as Bates loves Seattle and couldn’t call any other city home, he feels like there are places with better markets for his work, and he would like to get a point where he can focus solely on the act of painting. Like all working artists, Bates has had to make his peace with learning to be part businessman, and he would like to move away from the pressures of such things as marketing and promotion.

“I want to make work. And just make work,” he tells me.

(L and R) Untitled, gouache on toned paper, 9″ x 12″; (Below) Glacial Heart, cut paper and gouache, 8″ x 10″

“It’s one of the most rewarding jobs I’ve ever had,” he says without reservation, but he emphasizes that he would like to get to a point where it is not necessary.

While his current goals follow a fairly traditional artistic trajectory, Bates got his first start in an entirely atypical fashion, and it’s only by virtue of a series of tangents that the topic even comes up. Ready?

Because of the delicate, graceful nature of his work and the fact that he sometimes works in cut paper, viewers at times assume that Bates is female. Bates welcomes this confusion, and elaborates by saying that he feels like work should be judged on its own merits, not on any assumptions about the person who made it. From here our conversation jumps from the inherent perception of femininity in certain mediums to the relationship between work and persona, and this somehow segues into the idea of hiring a proxy to play the role of The Artist at openings, which in turn prompts a discussion of pseudonyms, which then leads to graffiti (“I appreciate the typography,” is the most flattering thing Bates has to say on the matter) and eventually ends up revealing the fact that Bates was once arrested for trespassing.

While his arrest happened in Seattle, he was moving to Michigan to attend the Kendall College of Art and Design, and was able to fulfill his community service working at Michigan’s Urban Institute of Contemporary Art. Bates speaks highly of UICA, particularly emphasizing their commitment to championing new artists, and he walked away from his community service with very practical skills. “I was able to learn about installing and deinstalling shows and all this stuff I wouldn’t have done otherwise if I hadn’t gotten arrested,” he laughs. “It was wonderful.”

Three years later, Bates, along with some of his other friends from art school, applied to do shows at UICA. “We all decided we should apply so we could get used to the idea of rejection,” he explains with an air of self-deprecation. But Bates’ show was accepted, and so he had his first exhibit at the Urban Institute of Contemporary Art. Bates jokes that he started strong and has only gone downhill from there, but he hopes to show at UICA again in the future.

For the time being, Bates is happy to keep his plans loose. He is relishing the freedom of his self-imposed retreat from the pressures of showing and constantly engaging with the arts community, and is looking forward to seeing where his creative meandering will take him.

www.joeybates.com

Ω