Bent on Literature

Initially concerned with designing engaging narratives with his painting, Sato learned to place storytelling at the center of his process. It was, as he calls it, “the stock of the semiotic soup I was trying to cook.” Sato’s focus on narrative, however, was at times a detriment to the organic realization of his pieces; his attempt at incorporating it into everything he painted often left him struggling to “jam narrative in where it didn’t belong.”

Initially concerned with designing engaging narratives with his painting, Sato learned to place storytelling at the center of his process. It was, as he calls it, “the stock of the semiotic soup I was trying to cook.” Sato’s focus on narrative, however, was at times a detriment to the organic realization of his pieces; his attempt at incorporating it into everything he painted often left him struggling to “jam narrative in where it didn’t belong.”

To solve this problem, Sato now prefers to let the work unfold as it pleases. “The paintings tend to be better when I let the emotional impact of the visuals and the joy of the materials lead the way,” he says. “That’s not to say that I’ve abandoned narrative painting. I still do it, but only if it comes along naturally and feels right, as opposed to storytelling always being the main goal.”

Words have always played a significant role in Sato’s life, and his penchant for storytelling may come from his interest in reading and writing. “[Writing] can be a really useful tool to clarify ideas or to break through some creative blockage,” he shares. “[It] feels like it comes from a separate part of the brain than where imagery generates from, so when I’m having trouble on a painting, I can turn to the writing to think about things from a different angle.”

Books, too, are particularly meaningful. “There seems to have been one major world-rocking reading experience per decade in which I’ve been alive,” he explains. “As a kid, it was From the Mixed Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler. I just read this again recently, and it’s still wonderful. In my teens it was nearly everything by Kurt Vonnegut.”

Particularly fascinated by Vonnegut’s Breakfast of Champions and Cat’s Cradle, Sato received the latter while he served a short jail sentence for the unlikely charge of Grand Theft Food. Sato and his friends were convicted of stealing 27 pounds of vanilla pudding and 19 boxes of bulk pasta from fraternity house kitchens in Berkeley, California – a crime serious enough to be slapped with Grand Theft – but silly enough to make the judge laugh. Ultimately, it was due to the length of his incarceration and the brevity of Cat’s Cradle that Sato found both annoyance and inspiration in the book. “I ended up reading it eight times in two days, and it didn’t get old. That’s a combination of that book being incredibly entertaining and jail being relentlessly boring,” he recalls.

In his late twenties, Sato’s interest veered to the unlikely lepidopterist and famed Russian novelist, Vladimir Nabokov. “I finally got around to reading Lolita,” he explains. “It’s probably the funniest, most disconcerting, most diabolical thing I’ll ever read.”

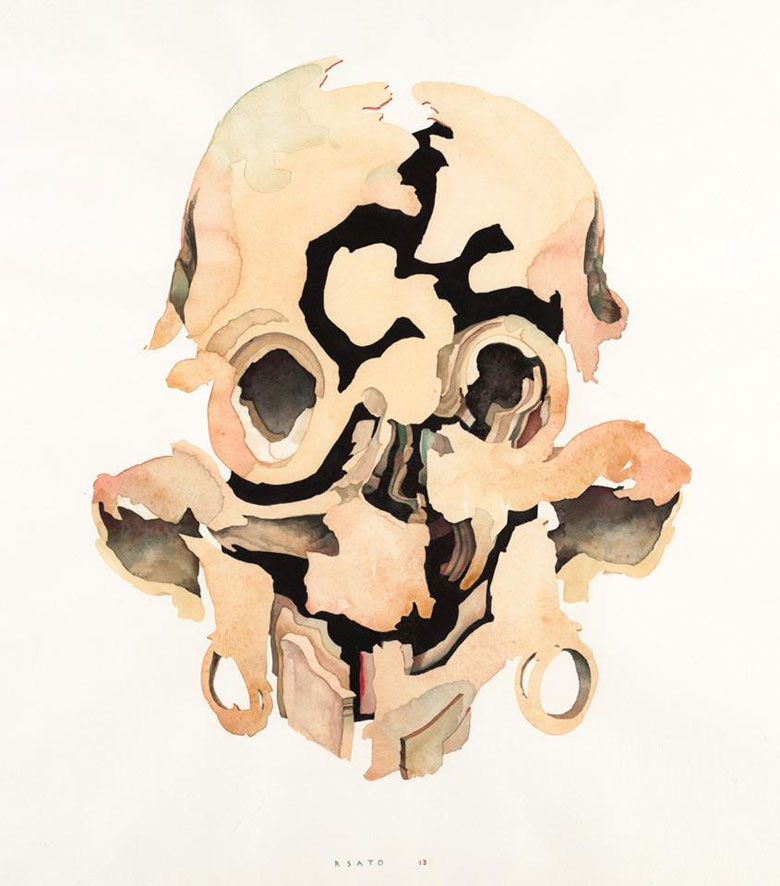

Freed by Restriction

Just as Sato’s reverence for words allows him the freedom to think differently, his use of watercolor is liberating by virtue of its limitations. “Watercolor simply isn’t as flexible as acrylic or oil,” he says of the medium’s limitations. “You can mix oil and acrylics with all kinds of stuff. You can correct mistakes and change your mind almost infinitely. You can also build a surface with oils and acrylics, sand them, scrape into them, beat the shit out of them. By contrast, watercolor is pretty much just water, paint and paper. It’s a delicate medium. Once a mark is made it cannot really be unmade, though the paint does reactivate somewhat when you rewet it, which becomes important when planning out how you want to layer your washes or glazes or how much fussing you want to do in a particular area. You have to improvise with a ‘mistake’ rather than correct or paint over it. For me, this limitation has been oddly freeing.”

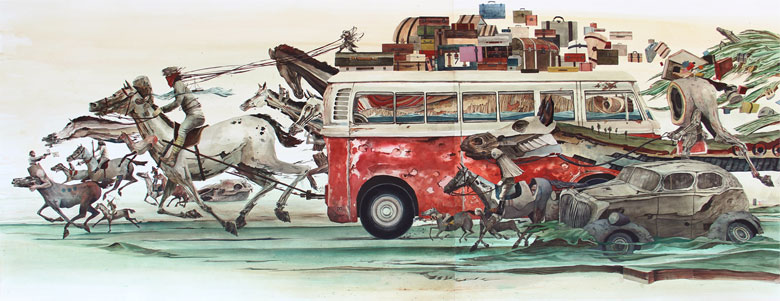

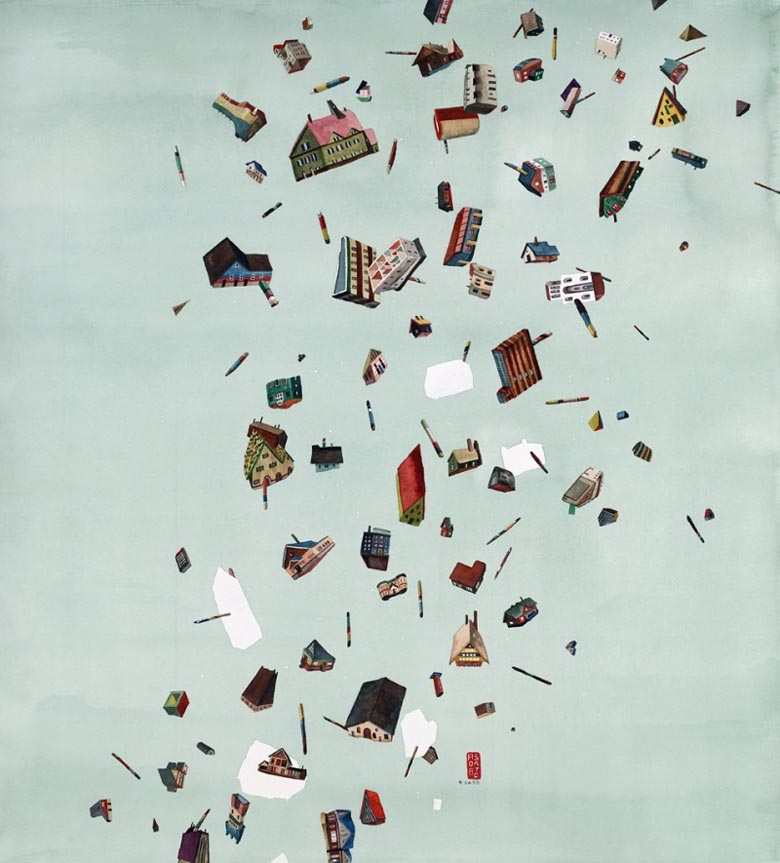

The confluence of his varied inspiration and the liberating nature of the medium manifests in many different ways. Some pieces come together quickly while others require more thoughtful design.

“Sometimes a piece is suddenly right there, ready to go, because all the elements for an explosion have come together. It’s wonderful when that happens. Often, I have no idea that I’ve been gathering those forces, and then, without thinking, they just get unleashed,” explains Sato.

This creates a raw and powerful result, but Sato admits to finding joy in longer, more conscious thought processes. “Sometimes there’s an idea that was just there but didn’t mean that much to me before, then suddenly it jives with things that I’ve been reading or writing lately or seems to relate to the world in a way that it hadn’t before,” he says. “Sometimes I just get an emotional charge from a composition, but haven’t figured out what to put into it or the right way to put it together. It’s really all about getting a piece to vibrate in some way so that it becomes a presence in the world that lives and breathes, a creation that is more than the sum of its parts.”

Inspired by the Subconscious

With elements of horror, grotesque transformations, and whimsical beauty, the images Sato creates suggest a certain subconscious meandering akin to the surrealist movement. He prefers, however, not to brandish this particular identifier. While he is fond of early surrealist theory as it is bound by imagery drawn directly from the subconscious, he feels the meaning of the term itself has been corrupted.

“I feel like most of what proclaims itself to be surrealism now (even a lot of stuff then, really) is over-manipulated, utterly but feebly conscious and repetitive imagery, lazily slurped from a depressingly shallow, lifeless myth pool,” says Sato, while even going as far as posturing that “the word surreal is better applied to life outside of the arts now.”

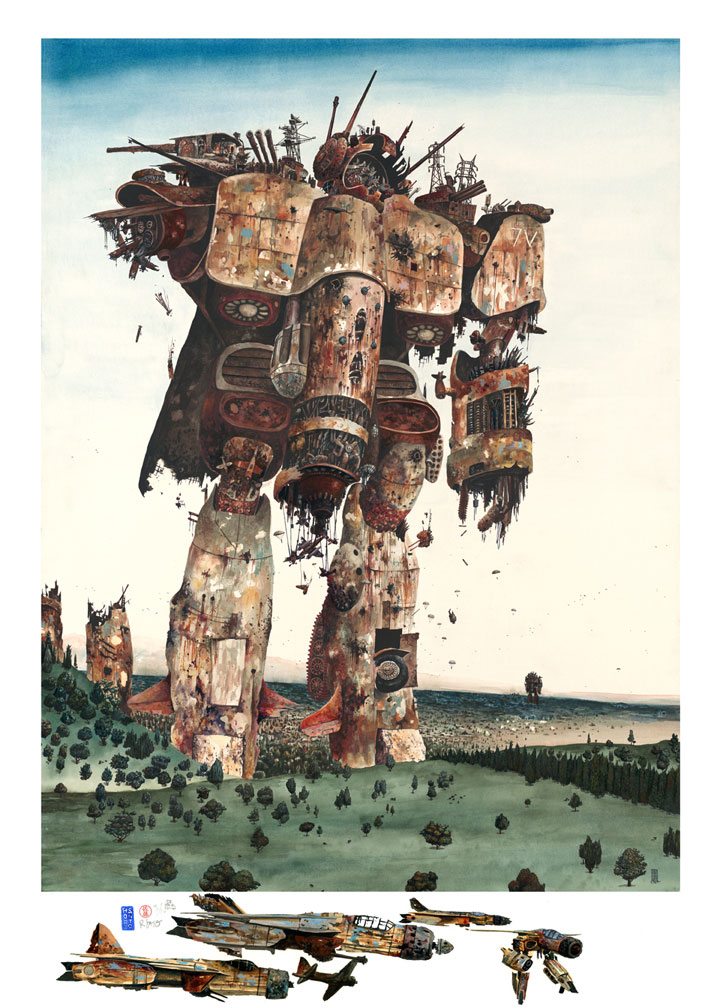

Finding a place where dreams and reality meet may be the ultimate objective, and this idea is perhaps most visible in Sato’s Peace at Last in a Future Passed — a painting where the reconciliation of fantasy and reality manifests as the struggle to accept the inevitable realities of adulthood. Maturity becomes the metaphorical slayer of childish aphorisms. The painting depicts a giant decaying robot speckled with dilapidated aircraft, electrical towers, and battle armaments. With one arm missing and decomposing bits falling from its massive form, the image is captivating whilst being disturbing.

“Future Passed [bridges the gap between fantasy and reality] in a different, much more specific way than any of my other work,” describes Sato, “by mixing my childhood fantasies of heroism and adventurism with more mature ideas and knowledge about the reality of war.”

While Sato’s thoughtful intent is clear within the details, it is the subtlety of color and the impetuous style of the brushstrokes that reveal something raw and wonderful. It is an affectionate struggle between real and imagined, and the harmony he seeks is daftly aided by his beloved watercolors. “There’s a joy in finding the balance between my controlling nature and the fluid chaos of the medium,” says Sato.

While armed with a headful of ideas, he is simultaneously committed to surrendering to the sublime. What makes Sato’s work stand out is that he is able to balance discipline with turmoil. This interplay between intellectual design and subconscious renderings results in a uniquely Sato-esque universe where dreams are both tantalizing and terrifying, and reality is a pliable concept.

Ω