Moroni For President, co-directed by Saila Huusko and Jasper Rischen, follows Moroni’s outreach in high school classes, at traditional dances, and elsewhere in the community, highlighting the complexity of his political philosophy and intertwined identities. Since the 2014 Navajo election, issues around Indigenous sovereignty have only become more pressing*, with tribes gaining some legal rights while also being targeted by the Trump administration. With Moroni For President‘s re-release two years after it originally premiered, it’s now the perfect time to recognize how prescient Moroni’s campaign really was.

Poster art by Samya Arif

Moroni styles himself as a hyper-educated populist who can easily switch from talking about decolonization to the need for new blood in Navajo leadership. Conversely, his main opponents have a populist aesthetic; as he wryly observes, the uniform for Navajo presidential candidates is blue jeans and cowboy hats—but eschew anti-establishment sentiments. In one telling moment, the favored candidate, Joe Shirley Jr., dismisses Moroni as a “professor from Washington state” who doesn’t understand Navajo politics. Even Moroni’s campaign manager says that Moroni approaches the Navajo people like students, but it’s unclear whether they want to take his class.

On election night, Shirley’s perspective is somewhat vindicated by Moroni’s smug reaction; upon learning that he finished 12th out of 17 candidates, the jilted Moroni tells a reporter, “These voters are not very bright.” Assuming Moroni made a gaffe, the reporter asks if he can get that on the record. Unfazed, Moroni repeats his quote.

With a professor’s desire for specificity, Moroni forcefully condemns what he sees as the empty rhetoric of the main candidates, declaring in a presidential debate, “The Navajo word of the day is ‘platitudes.'” Yet his idealism quickly clashes with political realities. At one point in the film, he sheepishly admits that when he went into “professor mode” when discussing decolonization and sovereignty, he sensed his audience’s eyes glazing over. Yet when he made powerful statements in simple terms about the Navajo people’s need to assert their own destiny, people seemed inspired. To more jaded observers of politics, these reactions are predictable—it’s often said that politicians should speak at a 6-8 grade level—but to Moroni, they’re baffling. “I’m confused by politics,” he says.

* The Navajo Nation in Mainstream American Politics

Nostalgic photos of the Obamas with past Navajo Nation presidents contrast with Trump’s hostile relationship with the tribe. Trump’s attacks on Native people’s sovereignty include his 2017 signing of an unprecedented proclamation to radically shrink the size of the Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante monuments in Utah. Both monuments are home to cultural and natural resources of indigenous people, including rock art, ceremonial sites, and fossils. The Bureau of Land Management recently released plans for Bears Ears, which opens the area up to increased tourism and intensive mining and drilling. (VIEW INTERACTIVE FEATURE VIA WASHINGTON POST)

More recently, the federal government blatantly violated indigenous people’s sovereignty by executing a Dine man named Lezmond Mitchell. Per the 1885 Major Crimes Act, the FBI has jurisdiction over some crimes committed on Native land, including violent ones. Yet the Navajo Nation in Arizona, where Mitchell committed his crimes, explicitly opposes the death penalty. In 2001, the attorneys general of both Arizona and the Navajo Nation recommended against executing Mitchell following his conviction for murder. But current attorney general Bill Barr chose to undertake the execution anyway, completely disregarding the sovereignty of the Navajo people. Mitchell’s death on August 26th marks the first execution of a Native person by the federal government since 1902.

Still, there have been some reasons for hope. In recognition of treaties from the 1800s, the recent Supreme Court case McGirt v. Oklahoma established that many counties in eastern Oklahoma are in fact tribal land. And in 2017, as a result of the Land Buy Back Program, the Navajo Nation gained around 155,000 acres. As the attorney general of the Navajo Nation, Ethel Branch, put it, “The opinion is a triumph for the Navajo Nation and for Indian tribes throughout the United States, as the court confirmed that energy and utility companies must seek tribal approval for rights-of-way across tribal lands.”

Although Trump’s executive order on Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante worries environmentalists and Indigenous rights advocates, the egregiousness of his decision has inspired more Native people to get involved in politics. In Utah’s San Juan County, several Navajo candidates opposing Trump’s order ran for county commissioner and won. Now, for the first time ever, Native Americans represent a majority of the county commissioners.

Pictured: Bears Ears National Monument – Hoon’Naqvut, Shash Jaaʼ (Navajo),[1] Kwiyagatu Nukavachi, Ansh An Lashokdiwe – via Bureau of Land Management and Wikipedia

Moroni For President demonstrates how Moroni’s campaign wasn’t just unconventional, but also historic. In the film, Moroni delicately navigates his identity, aware of the compounding complexities of being gay, Navajo, and Mormon. Early on, not wanting to be pigeonholed by his sexuality, he declares, “There are far more important issues right now than me saying I’m gay.” While driving from Seattle to Navajo Nation with his sister, he casually mentions that when he came out to his parents, he promised them he wouldn’t date. Despite this restrictive bargain, he doesn’t seem resentful; despite their discomfort with his sexuality, his family of devout Mormons fully support his campaign, serving as a small army of volunteers that supply food and help him paint canvas posters. In one scene, the only people who attend Moroni’s rally are Mormon missionaries his mom knows. While he doesn’t want to be defined by his sexuality, Moroni does wonder, almost indignantly, why more gay Navajo people don’t support him. After this comment, the film cuts to Shirley’s gay campaign manager rejecting the idea that his sexuality dictates who he should support. According to him, Moroni just isn’t qualified to be president.

In addition to the need for a “New Guard,” a central theme of Moroni’s campaign is the importance, and vulnerability, of Native people’s sovereignty. His campaign reflects his assertion, born both from academia and his lived experience, that “the Navajo Nation is occupied by the United States.” A scene with Moroni’s brother Bert provides a poignant example of this intrusion of the federal government. Bert, unable to get a loan from the U.S. government, is technically building his straw bale house illegally. He jokes that if anyone objects, he can invoke the treaty of 1868. Just as Moroni’s brother laments having to build his house on the U.S. government’s land, Moroni is ambivalent about speaking the colonizer’s language. His Navajo, he says, is merely “utilitarian,” not elegant like Joe Shirley’s. Furthermore, the fact that many young people don’t speak Navajo at all is “the result of colonization,” tied up with the history of forced assimilation in boarding schools and the Indian Placement Program operated by the Mormon church. His emphasis on Navajo sovereignty distinguishes him from the other candidates, who don’t seem likely to object, as Moroni does, to flying the American flag on Navajo election day.

Moroni For President ends with Moroni’s unsurprising defeat, but also with the unexpected victory of Russell Begaye, who beat out Shirley and the incumbent. Underdog Begaye calls Moroni’s campaign “refreshing,” and describes him as among a crop of new leaders. After his loss, Moroni tells a group of students, “We have to be willing to fail.” Yet in the end, his campaign represents less an unmitigated failure than an audacious experiment.

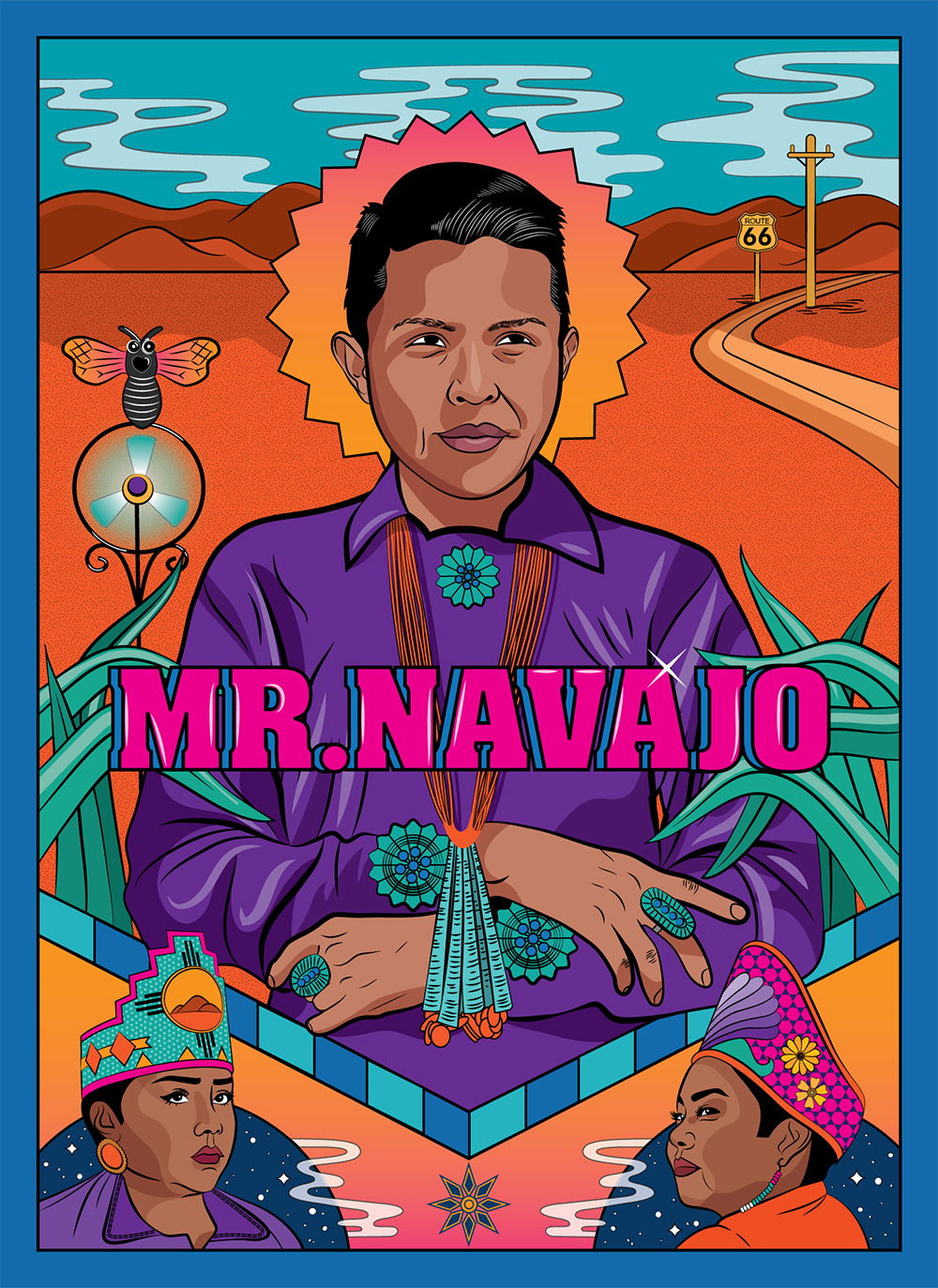

Mr. Navajo (2020) Short Film

Fhe film’s co-directors, Saila Huusko and Jasper Rischer, also released a short film earlier this year around Zachariah George — a twenty-five-year-old queer Native American who goes by the moniker of Mr. Navajo. George was directly influenced by Moroni and his campaign, and is both an LGBTQ advocate and a fervent defender of the Navajo language. View it online via NOWNESS.

Poster art by Samya Arif

Ω