Upon returning to the region as an adult, Gomes was baffled.

“When I passed by the road in Toritama, I saw the billboards in the middle of nowhere with jeans models, with paradise, and I said, ‘Oh my god, what’s that?’ The driver told me, ‘Toritama now is the Brazilian capital of jeans’ . . . ” he recalls. “When I got to Toritama, the city was completely polluted, the noise was completely oppressive, the city was a mess. I said, ‘Wow, this must be England in the first Industrial Revolution, like a hundred-fifty years ago, that people work, work, work. And the people don’t have free time to enjoy themselves.'”

“I was interested in the human environment,” he continues. “I was interested in the people — what changed in the way that they think about life, the way that they dream, the way that they think about the future.”

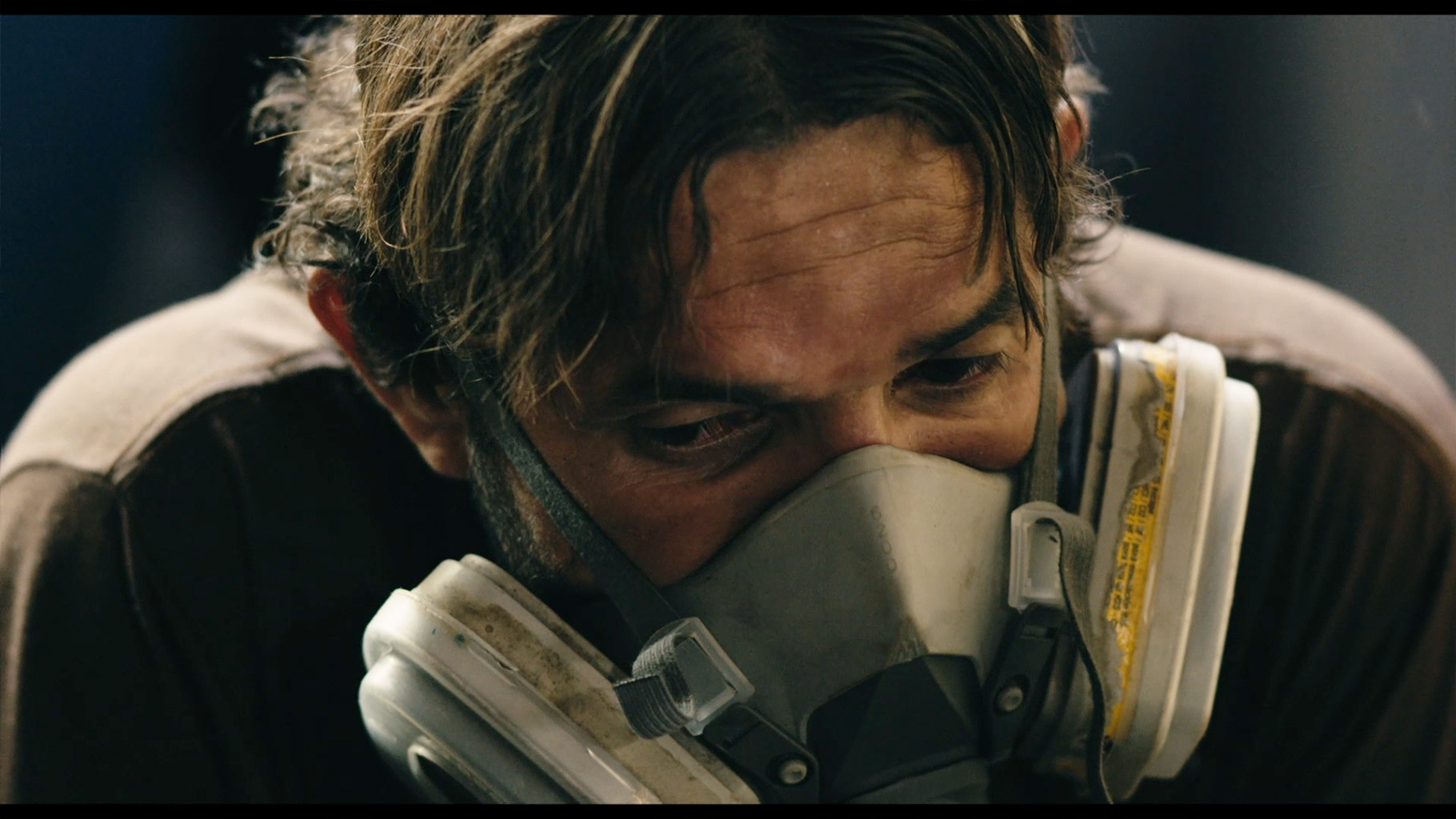

Indeed, throughout Waiting for the Carnival, Gomes continually juxtaposes the old and new Toritama, wondering how a quaint village became a jeans boomtown. The change is registered by all five senses, but particularly sound, as Gomes reflects on the cacophony of industry. The respite of lunchtime is now the only time the town returns to its original quiet. Waiting for the Carnival also finds a visual language for this large-scale transformation, weaving potent symbols throughout. Shots of the last remaining goat herder, who must traverse sidewalks and freeways to get his goats to pasture, take on an elegiac tone. Sometimes it seems that only the monsoon rains, which come like clockwork every June, have remained unchanged. With striking motifs of weather, Waiting for the Carnival is highly attuned to the natural rhythms of Toritama not yet eclipsed by human time clocks.

To Work for a Living or Live for Work?

Despite the melancholy tone, the film’s subjects, many of whom work in backyard factories called “factions,” repeatedly extol the virtues of being their own bosses and setting their own schedules. Rags-to-riches stories of lowly assembly line workers becoming faction owners abound. But the hours are long and the pay miniscule: 25 USD for making 1,000 hems, and 50 USD for making 1,000 zippers. A cadre of older women describe how they regularly work from 6am to midnight, returning home too exhausted to do anything but take a hot bath and plop into bed. Yet many say they feel lucky to choose when to take breaks for lunch and dinner, which are lively, communal affairs.

The domestic atmosphere of these workplaces also belies descriptions of them as “sweatshops.” In one scene, a young woman talks to Gomes while also wrangling her cat off her lap and scolding her toddler son for playing with one of the sewing machines. Meanwhile, the young men, many of whom became fathers at 19 or 20, bring a certain swagger to their work. Striding down the streets, they blast music and whip jeans in the air as though practicing a new dance move. Waiting for the Carnival vividly captures the chaotic entanglement of home and workplace, leisure and labor.

For Gomes, his subjects’ sanguine attitude towards the workload was surprising. “I thought [they were] going to complain about life, say that life is terrible, and they said the opposite!” he reflects. “They said, I have the freedom to decide the time I can work, to decide if I want to work or not. I am the boss and that’s why I’m happy.”

“That’s completely different from the 19th century in England,” he continues. “People had to work, work, work, and afterwards, they made some strikes, they made some unions, they decided that they have to have free time, holiday. They created labor laws for like a hundred-fifty years.”

His subjects’ different attitude towards work has implications for all of us, Gomes believes. “But now the new liberalism, the new idea, is, ‘Yes I can.’ I can make more money, I can work more. So all of a sudden, this film that was going to be about this city that for me was the past, became a film about, what do we do with our lives? What do we do with our time? Do we work for a living or live for work?” he questions. “I found out that Toritama is not the past; Toritama is the future. Because nowadays, with the internet, email, WhatsApp, and Zoom, we work from 9 to 9 and sometimes from 9 to 12. Our life is work.”

Carnival is the Soul

The film’s subjects latch onto the yearly, week-long festival of Carnival for both a reprieve and a sense of purpose. Yet despite its titular importance, Carnival is only first referenced near the end of the film. This unexpected sequencing cleverly puts the viewer in the position of the worker, who toils 51 weeks of the year for seven days of revelry. The film’s subjects eagerly sell their stoves, TVs, and motorcycles to loan sharks, knowing full well they’ll have to buy them back at a steeper price, just to pay for Carnival. One woman explains, “Gotta live for today. Only God knows what tomorrow will bring.” It’s a version of the YOLO ethic familiar to many American viewers. There’s more than a hint of FOMO, too, in the poignant scenes with teenagers who can’t afford to go, left behind to sit listlessly on stoops. They compare Toritama during Carnival to a “cemetery” and a “ghost town.”

For Gomes, Carnival is one of the few pockets of culture left in Toritama, which has lost music schools, libraries, and theaters since the jeans takeover. Even its spiritual centers now exalt work above all else.

“They don’t have music schools anymore. They don’t have libraries anymore. They don’t have a theater anymore,” says Gomes. “At all the evangelical churches, they promote the idea that work is good. In the name of God, you have to work 12 hours, 14 hours, 15 hours. The only cultural heritage that is left is the Carnival. It’s like in the States, the 4th of July; it’s like Thanksgiving. Carnival for us is really serious. Carnival to us in Brazil is like part of our soul. Since I was five years old I used to play Carnival. I think [it’s] the most important thing in our culture.”

From one angle, this deeply rooted love for Carnival makes the inevitable return to grinding work tragic, yet Gomes’ subjects largely accept the rules of their world without resentment. The work calendar and the yearly monsoon seem equally inevitable. Indeed, Waiting for the Carnival isn’t an exposé so much as a textured sociological portrait — a bottom-up exploration of a rapidly expanding industry. Waiting for the Carnival is a rich enough work to inspire divergent responses, and perhaps even raucous debate.

The completion of Waiting for the Carnival stirred passionate interest in Toritama. “I met the owner of the cinema [in Toritama] and I said, ‘I’m making a film about the city and I’m going to present the film in your cinema.’ And that was something unique,” Gomes recalls. “[It] was the first movie about Toritama. The film was there in the cinema for almost two months, and more people watched our film than watched Batman. Why? Because it was the first time that people could see themselves in a screen! They could see their lives, their actions, the way that they live, the place that they live.”

Beyond the billboards and advertisements, Waiting for the Carnival plunges the viewer into the lives of those who spin the world’s “blue gold,” otherwise known as the ubiquitous, humble pair of jeans. It is a world well worth visiting.

Waiting for the Carnival Film Trailer

Ω