With 28,900 butts in seats for 33 feature films and 25 shorts, the 20th edition of True/False celebrated independent non-fiction filmmaking from March 2th to 5th, 2023, in Columbia, Missouri. Some of...

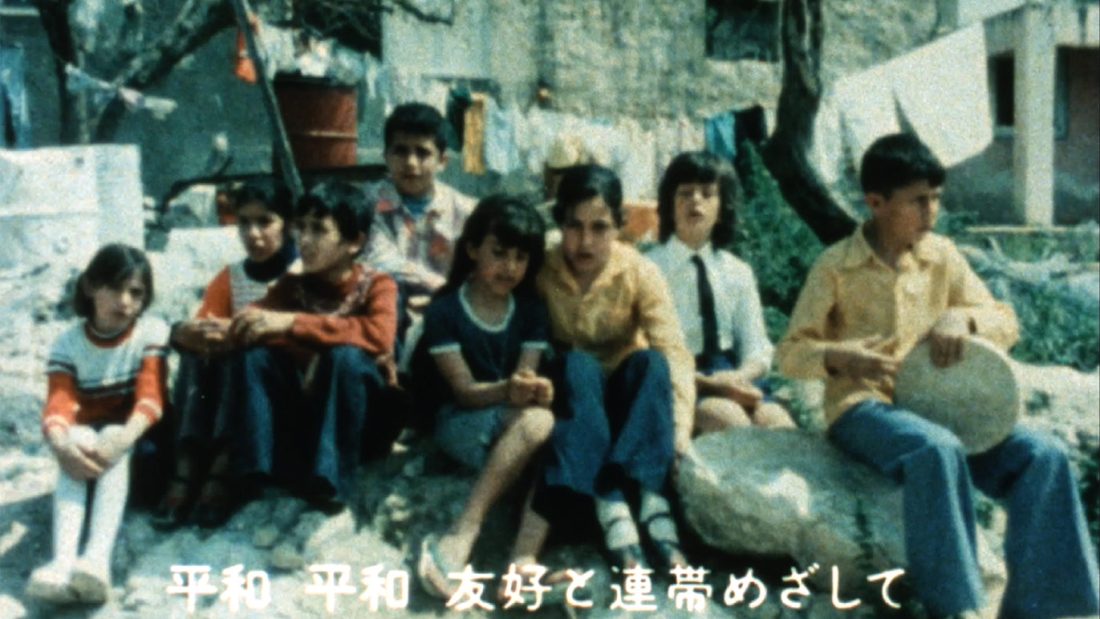

Read onBack in-person for the first time since the COVID-19 pandemic, the 13th Annual Seattle Asian American Film Festival (SAAFF) takes place in-person at Northwest Film Forum from February 23 to 26, 2023, and virtually from February 27 to March 5. This...

Terence Nance and I leapfrog through time and space. Numerous missed connections and mutual schedule misalignments occur until — two weeks later — we finally manage to get on the phone to speak about Nance’s new record, V O R T E X...

As Dallas musician Nicole Marxen details in the press release for her self-released debut EP, Tether, “I used to think that my life wasn’t worth writing about… I hid behind the characters I created, the haven of the stage, the...

In the Criminal Justice Club at Horizon High School in El Paso, Texas, students bond and gain camaraderie while also rigorously training for careers in law enforcement. Horizon’s program is the subject of At the Ready, filmmaker Maisie...

When Bonobo included Khruangbin’s “A Calf Born In Winter” on his 2013 Late Night Tales mix, he placed the strumming, shuffling, soulful instrumental between some late night ambient classical piano and his own “Get Thy...

"The interesting thing about working together to me was how easily and swiftly it all came together... There was probably a build up of the excitement of working together and trying new things and allowing each other this room to go wherever we...

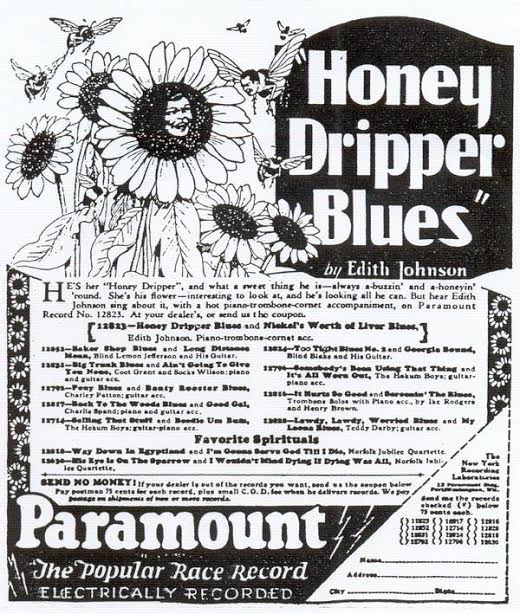

Folklorists like to romanticize blues music as being a pure expression of culture, but recorded blues music was carefully marketed to its intended audience from its very beginning. As early as the 1920s, music aimed at African-Americans was labeled...