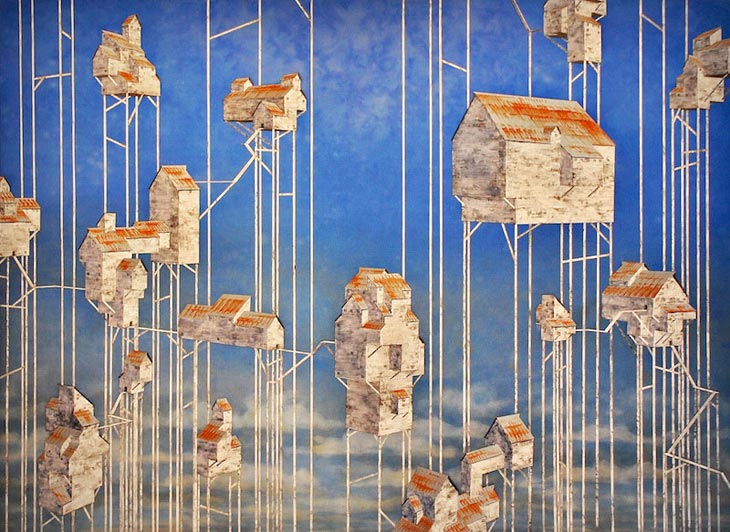

Mangan grew up in rural Washington but spent a number of years living in New York while attending graduate school at Hunter College. His interest in shantytowns and weather-worn buildings began with observations of his surroundings, and was later informed by the urban layering of New York City. “I think what [my interest] comes from is a combination of growing up here and always being attracted to these dilapidated old structures,” Mangan explains over coffee. “And then in New York, the overbuilt stacking, the literal hierarchy — where the higher up you are, the higher up you are. You look up and you see the penthouses, and then you look down and you go into a subway.”

When Mangan first began his explorations into rural Americana, he was working with a very unorthodox medium. “I was painting fairly realistic, naturalistic subject matter at that point, and I was frustrated, so I decided I would just use the dumbest material I could find — something that wasn’t meant for art making and wasn’t so precise,” Mangan explains. “So I just bought a cup of coffee from the local bodega and started painting with it.”

“Music does something kind of like poetry does. We can access music and listen to music and it doesn’t have the expectations on it that visual art does, to be important or meaningful or to have direct social commentary… There’s just something visceral and direct about it that I want to be in my paintings also.”

– Jeremy Mangan

Looking at his work, it’s hard to believe that Mangan managed to achieve such an impressive array of depth and tones using coffee, but he has always been a technically skilled artist. He attributes much of his painting technique to his time spent as an ice carver. While finishing his graduate degree, Mangan’s studio shared a building with Okamato Studio, the ice sculpting business of Takeo and Shintaro Okamoto. “They knocked on my studio one day and said, ‘Hey, I need to deliver this ice sculpture; I could use a hand with it.'” At first Mangan only helped with the deliveries, but he was gradually entrusted with more responsibilities.

Eventually they let Mangan try his hand at carving. “They gave me a 300 pound block of ice and a chainsaw and said, ‘Go for it.'” Mangan’s experience with carving fundamentally changed the way he approached painting. “As a painter, I could look at a face as a mug shot, and then in profile, and imagine how I would render it and how the line should be, but ice sculpture made me think in terms of volume, and that took a while to learn.”

This sojourn as an ice sculptor led Mangan to many interesting situations, including one assignment making a giant reindeer for Martha Stewart’s holiday party. “She seemed very… uh… composed. Like she was working. Very smiley, almost robotic. What you might expect.”

Although it was a day job that involved creating and working with his hands, Mangan ultimately felt that he needed to leave New York and make more time for the work he wanted to pursue. “I was working 40, 50 hours a week carving ice, and I didn’t go that far away to become an ice carver. It was just a job. I wasn’t painting… I joke that I needed to leave New York and move to Fife for things to really start coming together.”

Mangan’s work is deeply rooted in a sense of open space and images of countrysides, and one can easily see why he felt he needed to move out of the city to find his stride. His color palette draws heavily from the Pacific Northwest, and his pieces are juxtapositions of muted earth tones punctuated with intentionally garish bright stripes of paint.

“I’m drawn to local color, just from living here, just from soaking it up all these years. The colors that are added to the boards and the planks come from bunting and carnival colors. To me, it’s associated with this code or this signal, this sign of, ‘This is something important; this is something to look at.’ But most of the time it’s a weird, sad carnival or a car dealership, so I think it’s an interesting contrast within itself,” Mangan says. “You see those to represent something that’s supposed to be special or out of the ordinary, but oftentimes it’s not: it’s kind of pathetic and kind of weird… It’s celebratory and it’s supposed to be fun, but it has all these strange associations. I don’t think I’ve totally figured it out yet.”

While his paintings are most heavily influenced by his physical environment, Mangan also draws inspiration and support from belonging to a creative community. Mangan cites moving to New York as at best decision he could have made because it brought him into contact with “frenetic people with high caliber ideas” — friends who are still “influential on a day to day basis.” His process is also informed by music; specifically, by music’s ability to exist without what he sees as the necessary self-reflexive awareness of paintings.

“I think I’m envious of musicians,” he explains. “Music does something kind of like poetry does. We can access music and listen to music and it doesn’t have the expectations on it that visual art does, to be important or meaningful or to have direct social commentary… There’s just something visceral and direct about it that I want to be in my paintings also.”

Mangan’s work has been garnering some well-deserved attention in the past few years. He was the 2009 winner of Tacoma, Washington’s Foundation of Art Award, and is currently preparing for a solo show at Seattle’s Linda Hodges Gallery. Right now he is facing the problem all artists hope to have: “I have to make probably fifteen new pieces,” he laughs, saying, “almost all the paintings at my last show sold!”

Mangan is modest about his achievements and attributes much of his success to simple hard work. He advises aspiring artists to cultivate a blend of pragmatism and stubbornness.

“One thing I would say is, if you go to school for art, don’t spend a lot of money. It’s not worth it, it will really hobble you. It’s just self sabotage.”

Mangan also presents art school as a trial by fire, in which the goal is to instill the necessary tenacity to defend one’s ideas. “No matter what you do, professors will tear you apart,” he says. “They break you down. It took me a long time to realize that I think what it’s all about is doubt. They make you doubt and doubt and doubt until you finally stand up for yourself and go in one day and say, ‘No wait a minute; I don’t want to do X. I’m doing Y, and these are the reasons why… I’m going to keep doing it, and these are the reasons I think it’s interesting.’ And then they go, ‘Oh, okay.’… that was a huge lesson for me… any idea is valid so long as it’s done well and thought through.”

Mangan also acknowledges that not all projects will wind up in success, and that artists need to allow themselves a period of development in which they’re “not afraid to just make junk.” He emphasizes that the most important thing is to keep producing, and to not get discouraged when things don’t immediately come together. “If I want to be a professional, I think that’s the definition of professionalism — doing what you set out to do as best you can no matter how you feel about it.”

www.jeremymangan.com