Call it a spiritual treatise, a visual masterpiece, or whatever you like — but Alejandro Jodorowsky’s 1973 film, The Holy Mountain, has inspired musicians dating as far back as members of the Beatles, who played an instrumental role in funding and distributing the work. In this timeline of artistic individuals inspired by The Holy Mountain, we work backwards from the present day to the year in which the film was born, passing many music videos, songs, and philosophical shout-outs along the way. The creation of this timeline began with the intention of finding commonalities between the individuals who value Jodorowsky’s works, but the trend that emerged was much more varied than expected. More than anything, this timeline highlights the fact that though Jodorowsky influences many artistically-experimental thinkers, how they are influenced can sometimes be surprising, and is often completely unrelated to the author’s original intention and beliefs.

Call it a spiritual treatise, a visual masterpiece, or whatever you like — but Alejandro Jodorowsky’s 1973 film,

The Holy Mountain, has inspired musicians dating as far back as members of the Beatles, who played an instrumental role in funding and distributing the work.

In this timeline of artistic individuals inspired by The Holy Mountain, we work backwards from the present day to the year in which the film was born, passing many music videos, songs, and philosophical shout-outs along the way. The creation of this timeline began with the intention of finding commonalities between the individuals who value Jodorowsky’s works, but the trend that emerged was much more varied than expected. More than anything, this compilation highlights the fact that though Jodorowsky influences many artistically-experimental thinkers, how they are influenced can sometimes be surprising, and is often completely unrelated to the author’s original intention and beliefs.

NOTE: This is an ongoing article. We encourage submissions of other creative individuals inspired by this work, as well as suggestions for other timelines.

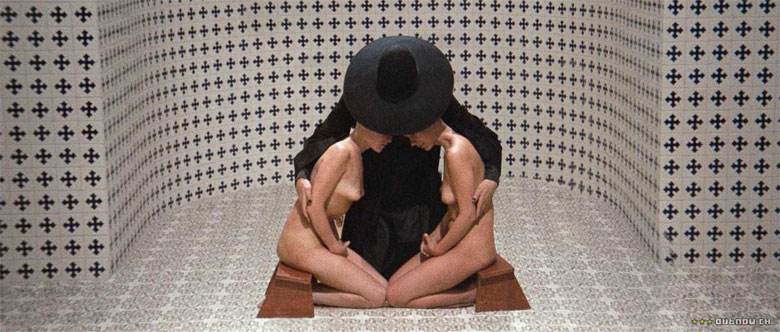

The Holy Mountain – Opening Sequence

“One can probably divide all these Jodorowsky fans into thousands of different cultural similarities, but for us it’s never about that. We never create our music from a template such as pop, rock or even instrumental. Maybe the movie, or Jodorowsky as an artist, is inspiring for daring to really leave your creative and personal comfort zone. Like, really, really, really leaving it.” – Kriget

2013

JUL

On their full-length

Dystopico, Swedish avant-garde trio Kriget create a earth-bending mix of instrumental music with their combination of bass, drum, and saxophone. “Holy Mountain” samples a musical refrain from

The Holy Mountain and sends it into droning, flickering, bass-heavy territories.

Questions answered by Kriget

Your track “Holy Mountain” is inspired by the film. How did that come about? Are there other ways in which the film has influenced your record or creative output?

First of all, it´s a fantastic movie — the theme in the song is influenced by the soundtrack and of course the name from the movie. The idea with our music is to open people’s minds towards music and arts, and if you scratch the surface you will see that there is more to it. And just like this movie, music doesn’t always have to be easy to understand; it’s supposed to challenge you.

What aspects of the film do you think are most striking to you? Aesthetics, philosophy, humor, etc.? Are there particular scenes which have made a lasting impact?

It’s the mix of all that, and like the Panic Movement proclaimed under their theater era, The Holy Mountain shows the audience what they don’t want to see — the unexpected — and if you mix that with things like fear, beauty and death you have the concept of “Holy Mountain”. It kind of visualizes the weirdness of life. The movie in itself can have a great impact on the viewer, but specifically one amazing scene is when the birds fly from the executed bodies. Like a delicate mix of cruelty and beauty.

The film is obviously an amazing visual treat; your music is very visually-evocative as well, and you have amazing music videos. Does the film at all influence your visual style or your visual interpretation of your music?

We’ve had the great pleasure to work with amazing artists on videos, like Moley Talhaoui (“Don’t Worry It Will Be Over Soon”), Marko Bandobranski (“Sleeping With Buddha”), Fredrik Joelson (“Holy Mountain”), Slobodan Zivic (“Submission”) and many more. It has always been a mutual creative understanding between us as a band and the great people that made our videos. The film as a visual masterpiece have probably not been that important for our visual presentation, but the mutual creative mindset between us and our collaborators has always been really important.

Compare Kriget’s “Holy Mountain” side-by-side with the song in the trailer for sonic similarities.

There seem to be artists that incorporate The Holy Mountain in a purely aesthetic way and others who apply more of a conceptual underpinning. What is your opinion on that?

The great thing about art is that you don’t really have to understand it. That’s the point. Sometimes people say that they don’t understand our music. That’s weird; it’s sounds of tones and rhythms. There are a lot of things that is hard to understand, like religion, wars and economy, but people tend not question that as much as art being constantly questioned. That is bothersome in some sense.

Before creating Holy Mountain, Jodorowksy employed methods of spiritual exercise, including Zen training, the teachings of Gurdjieff, and hallucinogens. Are you at all influenced by esoteric knowledge, psychedelics, rituals, etc.?

Yes, in an aesthetic way, it´s very exciting but it ends there. We are atheists and we believe that everything is possible, but you have to prove it first. Life is strange enough.

“I wouldn’t say the whole album is based off of the film, but it certainly inspired the title and structure. I like to get lost in my own train of thought while working on music. Sometimes it takes me to strange places; other times I end up where I started. Actually, most of the time my efforts don’t lead to anything! So naturally I have to be constantly working, sifting, shaping, transforming… It works out nicely, like a scavenging hunt out in the wild – eventually reeling in the big fish. The strangeness is what I associate with Jodorowsky’s films; they resonate with the unconscious.” – Úlfur Hansson

2013

MAR

On the press release for

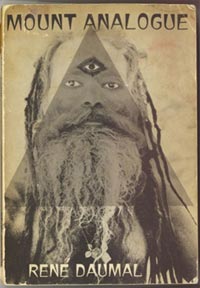

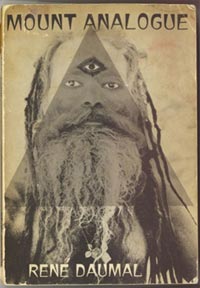

White Mountain, Úlfur Hansson says, “The title is a homage to Rene Daumal’s

Mount Analogue, as well as Alejandro Jodorowski’s film

Holy Mountain, but also something else….Each individual sound has a very special memory attached to it, so the album creates these nostalgic nonexistent spaces, hidden places – an amalgamation of instances, situations that couldn’t possibly exist. I imagine this White Mountain, an invisible imaginary place – a sacred place on the horizon. Maybe like a connection to the the universe above. An analogy of the journey of Man.”

Questions answered by Úlfur Hansson

How/when did you first discover the film? How did it inspire this record – or other aspects of your creative output – and what led to it?

My friend Sigtryggur Berg (of Stilluppsteypa) used to run this video store in my neighbourhood. He is a notorious film buff and would always come up with great suggestions when I came by. One time he insisted I watched Santa Sangre, and soon after that I had seen the whole Jodorowsky catalogue.

At the time, my record White Mountain was nearing its completion, and being immersed in Jodorowsky’s work between mixing sessions, the title was a no-brainer. Most of my song titles come from looking up from my computer at the keels in my bookshelf.

Mount Analogue also played a role [on your record], and it is my understanding that The Holy Mountain is based off of Mount Analogue. How, if at all, did you separate these influences creatively or conceptually?

René Daumal’s Mount Analogue was mentioned a lot in Jodorowsky’s Psychomagic. He talked about the book being his main inspiration for The Holy Mountain, so I immediately sought it out at the local bookstore.

There was one idea in particular that intrigued me while reading the book – the idea of the peradam – a rare perfectly round crystal, its spherical crystallization made possible due to the warped space surrounding Mount Analogue. The fact that it’s perfectly round makes the peradam near invisible to the naked eye – so for those who seek it, it is extremely difficult to find.

However, every now and then someone’s gaze will drift mindlessly, and at just the right angle catch a glimpse of the brilliant refraction of sunlight emitting from the peradam. This would only be possible when you are not looking.

That, to me, is analogous to the way creativity works. Art surfaces when you aren’t trying to hard.

“There is found here, rarely on the lower slopes and more frequently as one ascends, a clear and extremely hard stone, spherical and of variable size. It is a true crystal and – an extraordinary instance entirely unknown elsewhere on this planet – a curved crystal. In the French spoken in Port o’Monkeys, this stone is called Peradam. [It may mean… ‘harder than diamond’, as is very much the case, or else ‘father of diamond’… or ‘Adam’s stone’, and have had some secret and profound role in determining the nature of man.] The stone is so perfectly transparent and its index of refraction so close to that of air in spite of the crystal’s great density, that the inexperienced eye barely perceives it. But to any person who seeks it with sincerity and out of true need, it reveals itself by a brilliant sparkle like that of a dewdrop.”

— Rene Daumal, Mount Analogue

What aspects of the film do you think are most striking to you? Aesthetics, philosophy, humor, etc.? Are there particular scenes which have made a lasting impact?

The first scene is amazing. Kind of reminiscent of Matthew Barney’s work, even. I think this scene is a great example of the moments where Jodorowsky manages to capture the liminal: he can dance on the threshold of the grotesque yet beautiful; he can even capture something sublime and be funny at the same time. This also applies to Don Cherry’s contribution to the film, his music being very strange but not taking itself too seriously.

There seem to be artists that incorporate The Holy Mountain in a purely aesthetic way and others who apply more of a conceptual underpinning. What is your opinion on that?

I’m not sure it’s entirely possible to understand everything – if anything – about The Holy Mountain, and that’s what’s so intriguing about it! You can make up your own meaning, choose your own adventure. There is a lot of symbolism at work in the film, and symbols have the power to go beyond the meaning of words. Just like with occult studies, it’s important to formulate your own ideas on The Holy Mountain.

Mystical Weapons, a two-piece prog and post-rock outfit headed by Sean Lennon and Deerhoof’s Greg Saunier, is an unfocused and initially spontaneous piece of work that pulls its moniker from an arms manufacturer in

The Holy Mountain, named Isla. Isla creates weapons for peace protestors, with an impressive arsenal of psychedelic shotguns, grenade necklaces, and mystical weapons for religious folk (shown below).

Questions answered by Sean Lennon

Firstly, for Sean — obviously, your father and The Beatles were significantly influenced by and influenced Holy Mountain and Jodorowsky. Do you think that such reference points made your experience and understanding of the film different from that of those who may have just stumbled upon it?

It’s hard to say. Elvis was a big influence on The Beatles but Elvis didn’t influence me at all. So honestly I don’t think Joderowski’s impact on me had much to do with The Beatles other than that was how I first heard about him.

Mystical Weapons is named after the film. How did that come about, and are there other ways in which the film has influenced your record or creative output?

I’m not sure if the film had any direct influence on the record since we settled on our band name after we had finished the record already. Before that we were called Consortium Musicum, but we kept getting mistaken for classical musicians. That was our true motivation in changing the name. I often look at art and images I like to inspire my brain to think of titles.

ALEJANDRO JORODOWSKY’S MYSTICAL WEAPONS; IMAGES FROM THE STYGIAN PORT

What aspects of the film do you think are most striking to you? Aesthetics, philosophy, humor, etc.? Are there particular scenes which have made a lasting impact?

The whole film is incredibly iconic. There are scenes that stick out, but then every time I watch it I see something new. I don’t really understand the philosophy behind it, but I do understand the aesthetic, and I love that. I’ve never quite understood what was going on although I’ve heard many theories. I love the scene w all the Jesuses. The scene with the flame table. The scene with the Mayan frogs; although it’s very disturbing to see them explode, it’s certainly unforgettable.

The film is obviously an amazing visual treat; your music is very visually-evocative as well. If the film influenced this particular album, did it change your visual interpretation of your music after the fact?

Honestly our visuals have for a long time been about Martha Colburn’s short films. She is Mystical Weapons’ visual media member… Having said that, I do think that this band is specifically about the visuals that we play to live. I’m not sure how that will evolve in the future since Martha is very busy, but we will always find some visual element to pair with the live performances.

Before creating Holy Mountain, Jodorowksy employed methods of spiritual exercise, including Zen training, the teachings of Gurdjieff, and hallucinogens. Are you at all influenced by esoteric knowledge, psychedelics, rituals, etc.?

I’ve certainly read my fair share of all of that stuff. I wrote a paper on peyote when I was in high school, and used to read a lot of Terence McKenna and Carlos Castanedas. I’m not an especially superstitious person though, and don’t really believe in divination. I prefer particle physics to metaphysics.

The summery sounds of El Guincho’s “Bombay” pair up nicely with nudity, bright colors, and pagan imagery in this music video reputedly inspired by The Holy Mountain.

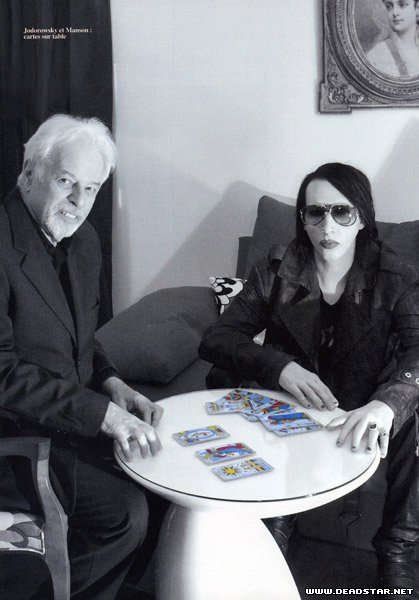

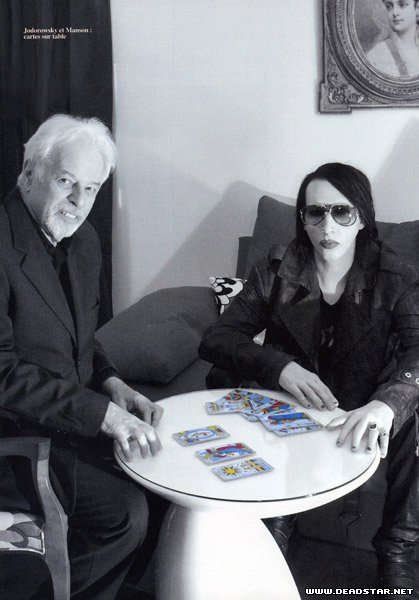

Jodorowsky and Marilyn Manson are mutual fans of one another and have a long and ongoing relationship. Below are some notable interactions:

In Alejandro Jodorowsky’s autobiography, The Spiritual Journey of Alejandro Jodorowsky, he details a scene in “The Dope Show” music video where Manson pays homage to The Holy Mountain:

I had stumbled on an interview with the rock star Marilyn Manson. His whitened face, reddened lips, Goth style, and sincere statements followed no script or rules, and I found myself fascinated by him. I sensed genius and exclaimed to myself: “With actors like him, I’d find stories to film again!” I made inquiries in the music and film worlds as to how to get in touch with him. I was told it was impossible. He received tons of fan mail and thousands of please for professional meetings, but he never answered any. I gave up.

Two weeks later, I was awakened at three in the morning by a phone call.

“Mr. Jodorowsky? I’m Marilyn Manson.”

I could not believe my ears. At first I thought someone was playing a bad joke on me, but it was really him–I did not have to go the mountain; it had come to me! He had called me to tell me that my films, especially The Holy Mountain, had inspired him so much that had made a clip in which he paid homage to it by imitating the scene in which the thief wakes amid cardboard Christs modeled in his image. He had even been inspired by the title to write a script for a film called Holy Wood, and he wanted me to direct him in it. I told him to send me the script by express mail. Two days later, I read it–a monumental, scathing attack on Hollywood. I realized that he would need about twenty-five million dollars to realize it. It was clear to me that he had no hope of getting this money from Hollywood producers, because they would never accept the ferocity of such criticism of their world. When I told Manson this, he understood. Instead, he offered to work on one of my projects. He heard that I wanted to make The Child of El Topo. I told him that it would be an honor and a joy to direct him in the lead role–but a legal obstacle prevented me from doing this film.”

On his personal Facebook, which is maxed out on friends, Jodorowsky has posted an interview he conducted on Marilyn Manson in 2007, which is excerpted below:

J: What is the definition of alchemy? It’s the spiritualization of matter and a materialization of the spirit. What is at the bottom is like what is at the top. A demon is an angel fallen to Earth, an angel is a demon raised to Heaven.

M: enthusiastically See why I like this guy! You really are the only person to understand these things…

J: A few years ago, every time a kid did something terrible in America, it was Marilyn Manson’s fault. Has this changed?

M: It’s became like in my personal life. As a human being, I was blamed for everything. Everything was my fault. I became a magnet for bad things in real life as well. A series of only catastrophes happened to me. Nothing good. Certainly during this time, Americans forgot about me a little, but I feel that with this record they will get back on my case. This new project is totally human. People will have to take it seriously. It’s even darker this time around.

In MGMT’s “Time To Pretend”, two specific scenes call attention to

The Holy Mountain, with cash being pushed into a burning hole (in a setting similar to the image below) and characters standing atop an ancient temple.

Late of the Pier’s pop song “Heartbeat” slips upwards and downwards through time, crashing through walls violently to enter into backdrops directly inspired by The Holy Mountain.

The music video for Santigold’s major hit, “L.E.S Artistes”, pays major visual homage to The Holy Mountain with the chaotic use of primary paint colors, violence, and smoke.

“Against The Peruvian Monster”, the opening track of Man Man’s debut full-length album, The Man in a Blue Turban with a Face, is named after a fictional comic book in The Holy Mountain. The thumbnail above is a still from the film.

On Agoraphobic Nosebleed’s second full-length, producer and guitarist Scott Hull hints at his love for The Holy Mountain, between thrashes, by including samples from the film.

Beck’s fifth studio album, Mutations, has two possible lyrical references to The Holy Mountain:

“Over the hill/ A desolate wind/ Turns shit to gold and blows my soul crazy” in “We Live Again” references the Alchemist turns the Thief’s excrement into gold.

“Holy Mountains/ They look so tired” in “Static”.

As we previously learned from

interviewing Arrington de Dionyso, the multi-lingual lover of William Blake, Kabbalah — and oh, you know, the infinite — is a lover of esoteric knowledge. Though his musical creations might not have a one-to-one correlation to

The Holy Mountain, the film has played an absolutely instrumental role in a philosophical and symbolic sense.

Answered by Arrington de Dionyso in 2013

How has Alejandro Jodorowsky’s The Holy Mountain influenced your creative output?

I think I saw Holy Mountain for the first time in about 1993 or 94 on a bootleg VHS, and at that time, I felt as though it were everything I had ever been looking for. It’s not just a film, but a container for a vast warehouse of esoteric teachings: alchemy, astrology, kabbalah, tantra, tarot, zen and ayahuasca are all in there. What’s particularly striking about The Holy Mountain is that symbols live and breathe with a numinous pulse. The film speaks symbols richly and profusely, but I think trying to break them down and “translate” the symbols into any kind of logical formation is a huge mistake. What does the movie “mean” is the same as asking what does the dance of life “mean” and that is entirely the objective of this very subjective work of art.

It’s more like a living painting that unfolds in time on the screen. A wildly pulsing and throbbing and dancing painting, spinning inside and out of the circle of life.

Adan Jodorowsky was born in October 1979 and is the son of Alejandro Jodorowsky. In 1989, he won a Saturn Award for Best Performance by a Younger Actor for his role in

Santa Sangre, and is now a successful tri-lingual musician, producer, and actor.

At the age of seven, James Brown taught him how to dance, and George Harrison gave him his first guitar lessons.

He has a role in Jodorowsky’s 2013 film, La Danza De La Realidad.

The Beatles, and specifically John Lennon, played an instrumental role in bringing Jodorowsky’s work to the masses. George Harrison as also considered for the lead role in The Holy Mountain.

It was on the recommendation of John Lennon that El Topo came to be brought and distributed in the United States and internationally, via Apple, whicstributed records by the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. Allen Klein, president of the company, wrote Jodorowsky a check for one million dollars to make any film he wished — also on the recommendation of Lennon. This resulted in The Holy Mountain.

In his book, The Spiritual Journey of Alejandro Jodorowsky, he gives an experience related to Harrison:

When George Harrison learned this company, Apple, was going to produce my film The Holy Mountain on John Lennon’s recommendation, he asked to read the script. Then he expressed a desire to play the lead role, that of the thief. Dressed completely in white, he received me in his elegant suite at the Plaza Hotel in New York. He offered me some melon juice with cinnamon and congratulated me on the script. He said that he was prepared to play the role on condition that we cut one scene, which he read aloud: “At an octagonal sink, next to a veritable hippopotamus, the alchemist bathes the thief, turns him over on his back, his buttocks facing the camera, and rubs soap over his anus.”

With an amiable grin, he said, “It’s quite out of the question for me to expose my anus in public.”

I felt as if the sky had fallen in. In those days, for me, a film was not a commercial or merely a work of art. I wanted this film to be the record of a sacred experience capable of enlightening an audience. For this, I needed actors–but only those who were prepared to put aside their egos. If Harisson played the lead role, it was important that he provide an example of total humility, exposing himself with the innocence of a child. This shot lasted only ten seconds, but it was vital to the work. It was obvious that if George Harrison played the role, the film would be assured of worldwide success, making millions–but this success would weaken the film, catering to the squeamishness of a famous musician. What a difficult koan!

Abruptly, and in total defiance of my own rationality, I rejected Harrison and hired a modest, young Mexican comedian to play the role of the thief. It was a choice between self-honesty and money and fame.

“There is found here, rarely on the lower slopes and more frequently as one ascends, a clear and extremely hard stone, spherical and of variable size. It is a true crystal and – an extraordinary instance entirely unknown elsewhere on this planet – a curved crystal. In the French spoken in Port o’Monkeys, this stone is called Peradam. [It may mean… ‘harder than diamond’, as is very much the case, or else ‘father of diamond’… or ‘Adam’s stone’, and have had some secret and profound role in determining the nature of man.] The stone is so perfectly transparent and its index of refraction so close to that of air in spite of the crystal’s great density, that the inexperienced eye barely perceives it. But to any person who seeks it with sincerity and out of true need, it reveals itself by a brilliant sparkle like that of a dewdrop.” — Rene Daumal, Mount Analogue

“There is found here, rarely on the lower slopes and more frequently as one ascends, a clear and extremely hard stone, spherical and of variable size. It is a true crystal and – an extraordinary instance entirely unknown elsewhere on this planet – a curved crystal. In the French spoken in Port o’Monkeys, this stone is called Peradam. [It may mean… ‘harder than diamond’, as is very much the case, or else ‘father of diamond’… or ‘Adam’s stone’, and have had some secret and profound role in determining the nature of man.] The stone is so perfectly transparent and its index of refraction so close to that of air in spite of the crystal’s great density, that the inexperienced eye barely perceives it. But to any person who seeks it with sincerity and out of true need, it reveals itself by a brilliant sparkle like that of a dewdrop.” — Rene Daumal, Mount Analogue

[…] the greatest sci-fi movie never made, having just come out, and an ever growing influence over pop culture, now is a good time to check out his work. All I can say is that I’ll miss writing about him […]