JJJJJerome Ellis stands with his hands clasped in the middle of a sidewalk. Photo by Marc J. Franklin

JJJJJerome Ellis stands with his hands clasped in the middle of a sidewalk. Photo by Marc J. Franklin

“My very first artistic e-e-excursions were in elementary school i-i-in this competitive improv theater troupe that was just amazing,” Ellis recalls. “We would receive prompts and then have to create and improvise skits based on the prompts. I absolutely adored it.”

Ellis speaks with a stutter — more specifically, a glottal block — a form of speech dysfluency that creates silent gaps in his speech that he calls “clearings,” often without warning and sometimes for prolonged periods of time. For most of his life, these clearings became unintentional performances of improvisation.

“S-s-stuttering has a very specific relationship with improvisation in that: when I sense I’m going to stutter on a word, for most of my life, I would try to avoid that word by using a synonym or something,” he reflects. “I-I-I had to be poised to change my sentence or the syntax of my sentence very q-q-quickly.”

JJJJJerome Ellis stands with his hands clasped. Photo by Marc J. Franklin

JJJJJerome Ellis stands with his hands clasped. Photo by Marc J. Franklin

The Radical Possibilities of Stutter

Ellis has come to embrace his stutter, no longer engaging in a constant dance of trying to sidestep these blocks in speech, but his love for performance and improvisation remains strong. By weaving recordings of spoken passages from the original academic essay together with ambient soundscapes, trap beats, and jazz improvisations, Ellis turns essay into performance, a way to embody and explore the radical possibilities of his stutter across an hour-long album. In this way, the listener is invited to experience the stutter, to witness the ways it disrupts rigid definitions of linear time, to cultivate patience in the face of the unknown.

The decision to incorporate music with academic essay arose out of his awareness of the fraught tensions within academia and music for Black people.

“The academy has such deep history in white supremacist p-p-practices a-a-and people of color have long been excluded from the academy,” Ellis notes. “And then there’s trap music — and Black music more broadly — which has been portrayed by certain people as u-u-uneducated or anti-intellectual. And of course, I don’t believe that. I believe that so many Black musicians are as fundamental theoretically as certain academics, you know?”

Over the course of 12 tracks, The Clearing became a way for Ellis to bring these two worlds of discourse that do not often overlap together. He jokes that he was curious to know what it would be like to “shake your booty while listening to an essay.” And yet, the bridging of worlds here is a serious decision — one that rejects harmful stereotypes about Black music and Black people through the act of subversion.

“I spend a lot of time reading academic writing and always have been drawn to it,” Ellis says. “I have also for a long time been very interested in subverting it and dissolving and blurring the borders between d-d-different forms of arts.”

Accessibility Through a Multiplicity of Media

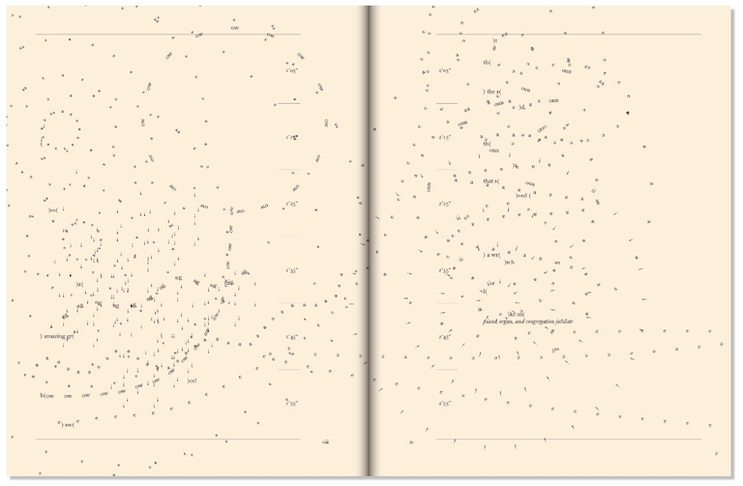

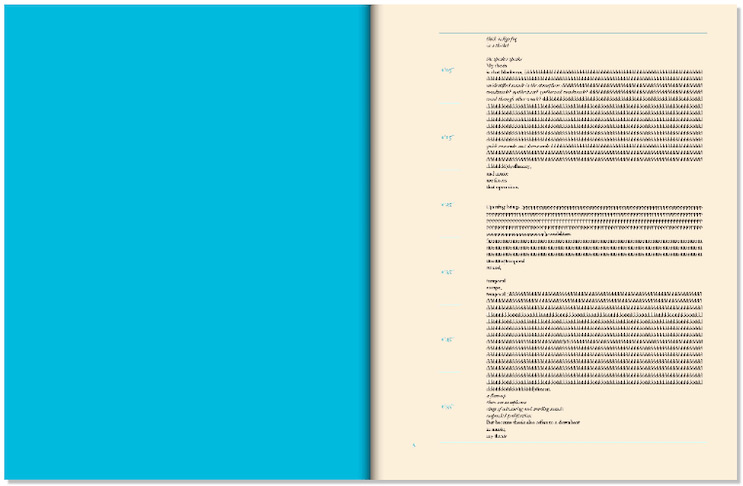

The Clearing is accompanied by a 98-page book of the same title, with a beautiful light turquoise cover. Each page corresponds to one minute of a track, not only charting the lyrics, but also noting — in increasingly experimental fashion — Ellis’ stutter as he speaks. Additionally, there are lines of italicized text interwoven with the lyrics. The preface explains that these are descriptions of the audio, but they feel more like poetry; Ellis describes synthesizers as “a child leading us to a new trail” and saxophones as “tongues of fire.” The practical origin of these italicized passages, Ellis explains, is to offer deaf and hard-of-hearing folks a way to experience the music through text.

“I identify a-a-as a disabled or Crip artist, and it’s important to me within that political identity to be cultivating Crip and disability practices across a-a-a range o-o-of disabilities,” he elaborates.

This sentiment builds on a previous project that Ellis worked on with Shannon Finnegan and Bojana Coklyat called Alt Text as Poetry, which explores how to fold accessibility practices into art itself, rather than treating them as a box to be checked off.

“I was interested in blurring the border between book and album,” he says. “C-c-can a book be a performance? Can a record be a score?”

Opacity & Illegibility as a Form of Resistance

The Clearing thrives on subverting rigid boundaries and embracing gray areas. Ellis draws on Scenes of Subjection by African American literary scholar Saidiya Hartman, where she discusses opacity and illegibility as a form of resistance for Black people. Embracing illegibility becomes important when understood in relationship to what Hartman calls the “hypervisibility of the slave” — where Blackness is immediately legible on a person’s skin and in their hair, thus exposing them to vulnerability and violence. Ellis takes this notion of opacity into the realm of sound, centering speech dysfluency as an act of resistance to the ways in which language and fluency have been used to police Black people.

“I think about the visibility of my skin a-a-and then the much more fraught audibility of my stutter,” he says. “In COVID, especially when I’m wearing a mask, it can be hard for people to tell that I’m even stuttering because they can’t see m-m-my mouth. I grapple with this so much because I want to be understood, but I also see so much value in the experience where you don’t immediately understand what’s happening.”

Nothing demonstrates this moment of opacity and misrecognition better than the fourth track of the album, “The Bookseller, Part 1.” A recording of a phone conversation, the track follows Ellis as he calls Barnes & Noble to inquire about a book. When asked for the title of the book, he catches on a glottal block. The bookseller asks if the connection is broken, but Ellis cannot respond and the bookseller eventually hangs up, assuming that the line is dropped.

“Something that I think about a lot in ‘The Bookseller, Part 1′ is that the decision to hang up is to me a failure in some ways of a certain kind of respect and a certain kind of patience that comes from respect,” Ellis reflects. Ellis has a love for plants and trees and compares this interaction to the moment he encounters a tree that he cannot identify. “There will be [a] tree I’ll come upon that I don’t know how to identify. I think that moment is so important because, for me, it so often leads to a form of respect. Sometimes it’s really important t-t-to just stand in humility before something that I don’t know.”

Across the album, we return to phone calls as skits. Ellis drew inspiration from SZA’s 2017 album Ctrl, noting that her phone call with her mother was particularly impactful.

“I wanted to emphasize that stuttering is so much for me about dialogue a-a-and conversation,” he explains.

Stutter as a Means to Open Up Time

In the album’s second phone call, “The Bookseller, Part 2,” Ellis again contacts Barnes & Noble and informs the bookseller early on that he has a stutter. This time, he is able to give the title of the book without being hung up on. The third phone call, which takes place in the eleventh track titled “Milta,” has a much different feeling. Here, he speaks with his mentor Milta Vega-Cardona, who appears earlier on The Clearing with a poignant reflection on how she sees Ellis’ stutter as a space that transcends linear time, granting him a connection to his ancestors.

“Milta feels to me l-l-like a spiritual mother,” Ellis shares. “I was interested in a journey of phone calls: one phone call where I’m hung up on, the second one where I disclosed this stutter, and the third where the phone call is so nourishing.”

This exchange between Ellis and Vega-Cardona is full of warmth, patience, care, and laughter, offering a stark contrast to “The Bookseller, Part 1.” The conversation reveals the beauty of the stutter: that it can — if we are receptive — open up time. The stutter asks us to slow down, to sit with patience and humility. Ellis wanted to acknowledge the expansiveness of time in this moment, and he does so with another gesture that can only be experienced in the book.

Throughout the book, there are timestamps in blue that are placed along the inner spine, a way to measure lyrics and music moving in real time. But in this conversation, the blue timestamps are replaced by fragments of a poem. Here, time quite literally changes; vanishes.

“That’s how I felt in that conversation,” Ellis explains. “That conversation is so generous and healing that I wanted to convey some of that.”

This reframing of time builds on “Legal Tender,” a poem by Kyle Dacuyan that conceives of sex as its own unit of time. “It hit me so hard when I heard that. The clock is only one way of many of measuring time,” says Ellis. “What if time is measured by these fragments of a poem?”

When Vega-Cardona tells Ellis that his stutter creates “access to the ancestors,” the imagery sounds beautiful, but what that connection allowed was initially unclear to me. Ellis explains that, in his case, his stutter was passed down genetically.

“How far back does that lineage go for my stutter?” he asks. “I think about all the generations passing down this form of oral p-p-possibility. That is so healing for me to then think of it, like it connects me w-w-with my ancestors in a very specific way.”

This connection to his ancestors has allowed Ellis to shift his thinking from lamenting his stutter as a curse and a pathology to seeing it as a gift — as an heirloom that he needs to steward.

“Trying to think of stuttering in terms of an ancestral c-c-continuity has helped me heal from a lot of the shame and pain that I’ve experienced around stuttering,” he reflects. “It’s like something that I need to take care of a-a-and preserve because it has value.”

Although The Clearing may be 12 tracks, my experience listening to it felt more like encountering one continuous, hour-long work. I asked Ellis how he has been thinking about translating the work to live performance in the future.

“I’m curious about how much alteration the work c-c-can take,” he tells me. He explains that it is not his goal to recreate the album word for word, sound for sound, but rather to communicate the essence of the work in a live setting. “There’s this whole thing. There’s this album, this book. How can I convey the essence of it and in this moment?”

With the launch event in mid-November in New York City, Ellis performed a portion of “Loops of Retreat” and then spent an extensive amount of time listing 40-50 names of some of the many people that contributed to the creation of the work before continuing on with two more tracks from the album. Ellis insists that placing this in the middle of the performance rather than at the end was a way to emphasize that it was important to him to give thanks and that it was not separate from the performance.

“The Clearing is also about gratitude and gathering,” he says. “Reading a list of thank you’s is as important as and in some ways even more important than p-p-performing ‘Loops of Retreat’ or whatever.”

This kind of creativity in his approach to performance coupled with his warmth, graciousness, and humility are what make Ellis so special and exciting, both as an artist and as a human being.

“For me, The Clearing is actually so minimal,” he reflects. “It’s this album and book and all this stuff, but it’s also just a space of possibility. Like you and I are in The Clearing right now and all we really need is humility in the face of the unknown and some patience and listening to each other.”

Listen to The Clearing

The Clearing is out now on Northern Spy Records / NNA Tapes.

The Clearing limited transparent 2xLP record bundle with book!

The Clearing limited transparent 2xLP record bundle with book!

Ω