Learning, Preserving & Revitalizing Language

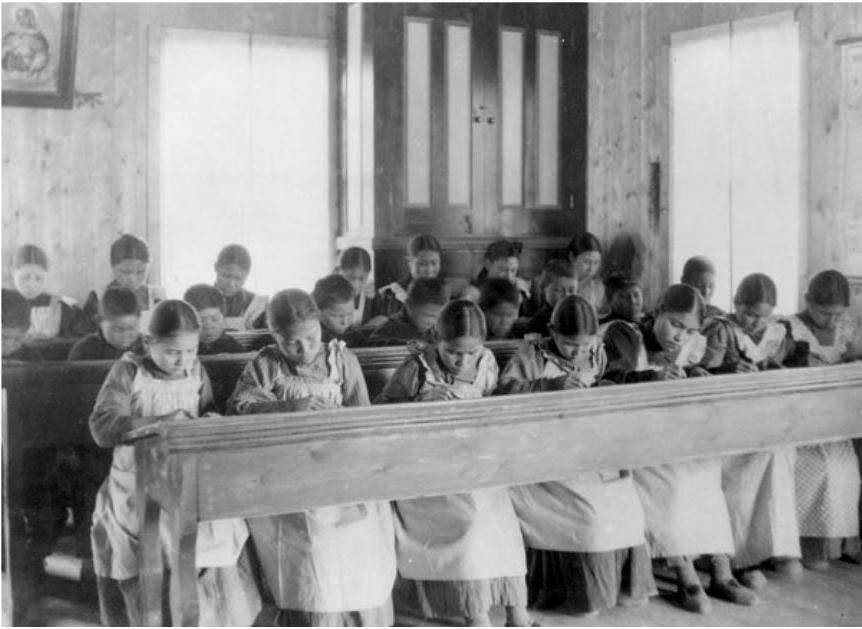

Canada’s era of residential schools, which began in 1831 and spanned over 150 years, mirrors a similar era of boarding schools in the United States. Both took Indigenous children away from their families and communities, forcing them to exist in educational systems that stripped them of their languages and cultures, as well as subjected them to widespread abuse and death. The repercussions last to this day — most visibly in the form of mass graves, which continue to be unearthed, and, less sensationally, through persistent intergenerational trauma due to cultural genocide and forced assimilation.

The intentional erasure of Indigenous languages — and with it, the loss of intricate, irreplaceable knowledge that is held by them — remains one of the most significant and detrimental acts of residential school violence. For some musicians, reclaiming the richness of language which has been lost is a central focus of their artistic energies.

Among them is Fawn Wood, a Nêhiyaw (Cree) and Salish singer based in Alberta, Canada, who comes from a family that is deeply rooted in traditional music. Her father and uncle are co-founders of Northern Cree, a drum and singing group that is well-known in pow-wow circles; her mother’s side of the family has “strong, powerful Indigenous women” who sing round dance music, which historically has been dominated by male composers and singers.

Nonetheless, because both of her parents went through the residential schools and lost their language in the process, even Wood has had to actively work to reclaim her Cree. She began her multi-year language journey at University nuhelot’įne thaiyots’į nistameyimâkanak Blue Quills, which is now a first-of-its-kind, First Nations-owned and -operated university. Ironically, it is also the site of the former residential school where Wood’s father lost his language.

“I felt more connected with myself after I learned the language, and I felt more connected to my community,” says Wood. “Just having that traditional worldview was almost like something was switched on in me. … There was a whole lifestyle. There was a whole history and teachings and traditional practices.”

Language has played a similar role for 9a (pronounced “nee-nah”), an Oglála Lakȟóta artist from Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. As an LGBTQ+ pop musician who identifies as bisexual, polyamorous, and gender-expansive or nonbinary, 9a finds that deepening their relationship to the Lakota language has helped them gain a deeper understanding and acceptance of self.

“Language is so important, because much of it still holds a lot of that blueprint for us to be better people,” says 9a. “It’s helped me check my internalized misogyny, or my internalized racism … and helps me connect to who I really am.”

Over the years, 9a has relearned their language and increasingly incorporated Lakota into their musical releases. Their debut full-length, matowin will be released in November 2023. It and their following four releases will be performed exclusively in Lakota, capping off a 9-chapter story titled “The Oglala Wolf Puppy with PTSD,” which they’ve been bringing to life since 2016.

“Lakota, in reality, doesn’t obviously translate to English at all, and much of what has been accepted as translation is just the closest interpretation,” says 9a. “In my language, everything almost inherently has a lot more depth; you can break down certain words, and … each of those have meanings. It’s just such a complex language, yet at the same time … especially within our beliefs, it’s very much innately within me.”

When it comes to Indigenous languages, intergenerational influences cannot be discounted. Elders play a key role in passing on knowledge and ensuring proper usage, especially as tribal language revitalization efforts grow.

Afro-Indigenous hip-hop artist Arias Hoyle, also known as Air Jazz, is the youngest member of the dynamic 10-piece rock band, Khu.éex’. With members from throughout Washington State and as far north as Juneau, Alaska, Khu.éex’ has numerous songs in Tlingit and Haida, and sometimes retells traditional Alaska Native stories through performance and spoken word.

As one of the band’s emcees, Hoyle has dedicated himself to learning Tlingit, driven by the lack of other speakers in his family and inspired by early memories of speaking Tlingit with his great-grandmother.

“I thought it was kind of both a responsibility and a motive for me to start learning the language,” says Hoyle, whose newfound grasp of the language has illuminated opportunities for deeper cultural connection, including through programs that are run by “more well-known and renowned Tlingit elders.”

“I definitely think [the Tlingit language] manifests in a lot of the values and the practices of our people,” Hoyle explains. “For one, every time they discuss something like weaving, cedar baskets, berry picking, or even hunting, they usually do so through Tlingit practice and tradition, while speaking the language.”

“When you reach out to [the elders] in the Tlingit language, they are just in your corner,” he continues. “They support everything you do from there on out.”

Khu.éex”s guitarist and multi-instrumentalist, Captain Raab, who is Siksiká, has decades of experience as a touring musician, including a stint with the well-known Native band Red Earth, which formed in 1997. He notes the changes across Indian Country over the years, saying, “There’s more language education programs going on in tribal communities, to where younger people are definitely more fluent in languages than I think my generation is.”

Like their elders before them, musicians like Sihasin and Fawn Wood actively consider how they will pass their knowledge on to future generations. Wood incorporates Cree into her music to encourage others to sing and speak it; Sihasin offers reminders through their band name.

“Sihasin, in our [Diné] language, [is] ‘hope, to have assurance, to look towards the future and plan, with a positive mindset,'” says Jeneda Benally. “That’s all just one word, sihasin, and there’s so much more within that as well.”

Sihasin came to their band name after a series of challenging circumstances. In 2009, they sued the federal government concerning challenges around the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). They hoped to protect the holy San Francisco Peaks from a ski resort’s on-site use of reclaimed wastewater, due to concerns about the endocrine systems of youth who might ingest the snow, and the effect on medicinal plants tribes gathered from the area. Three years later, however, they lost their case.

“It was beyond painful to me to have the reaffirmation that there was no justice in the judicial system for Indigenous peoples of the United States,” Jeneda Benally recalls. “At the same time, within weeks of that, there was a youth pact suicide of 13 youth from a remote area on on our homeland. … The youngest youth was 9 years old, and that further broke my heart.”

While Jeneda Benally spent much of her musical career using anger as a tool to motivate, create, and ignite, these tragic incidents led her to reevaluate the legacy she wishes to leave. The Benallys began to write new songs as therapy — and were reminded along the way that sihasin is fundamental to Diné lifeways. The philosophy, according to Clayson Benally, integrates one’s thoughts with planning and action, towards hope and an “assurance that everything will work out.”

“It felt like sihasin had been missing from a lot of our communities,” says Clayson Benally. “[Hope is] such a powerful form of expression within our culture, and I don’t think a lot of our youth even knew what that word meant, so we wanted to just bring that to the forefront.”

- Introduction

- Defining “Indigeneity” on One’s Own Terms

- Incorporating Tradition in Contemporary Music

- Learning, Preserving & Revitalizing Language

- Focusing on the Land & the Environment

- Raising Awareness Around MMIW/P

- Using Film as a Medium to Elevate the Collective

- Uplifting & Empowering the Youth

- Facing the Challenges of Visibility

- Building Infrastructure for Change

- Dreaming the Future

[…] min read29 seconds agoAdd comment I haven’t even stepped foot into the Snotty Nose Rez Kids show, and I already notice a couple things outside the venue. Clearly, the Indigenous fashion is […]