Baltimore’s Black Music Scene

In Baltimore, Maryland, aspects of the music scene were intimately connected to the city’s successful black capitalists. Rufus Emmanuel Mitchell, aka “Mitch,” operated Carr’s Beach, a segregated music resort near Annapolis that catered exclusively to African-Americans throughout the ’50s and ’60s, bringing in national talent such as James Brown, Otis Redding, and Chuck Berry. This gave Mitchell a strong connection to outside musical talent as well as a reputation on the East Coast as a premier musical entrepreneur. Mitchell was also an associate of William Adams, better known as Little Willie. Little Willie ran a numbers racket in the city which eventually became profitable enough to allow him to operate as a venture capitalist and bankroll a number of African-American businesses.

One such business was the record label Ru-Jac Records, run by Mitchell. Though Ru-Jac was mostly a passion project, it nevertheless issued a number of records between the early 1960s and late 1970s and became a way for Baltimore musicians to occasionally break into the national scene. Otis Redding, a friend of Mitchell’s, ended up recruiting Arthur Conley, one of Ru-Jac’s artists. Together, they released “Sweet Soul Music,” which became a hit — though many of the musicians, such as Winfield Parker and Joe Quarterman, stayed close to home in Baltimore.

Since 2002, Kevin Coombe, aka DJ Nitekrawler, has run DC Soul Recordings, a project which catalogs soul musicians from Washington D.C. and Maryland.

“The mystery behind Ru-Jac fascinated me during the early 2000s, when I first started digging up singles,” explains Coombe. “There was literally no documentation of this massive label anywhere. I spent the next decade and a half tracking down information, media, and people who’d been involved with Ru-Jac.”

Coombe saved, and now owns, the entire contents of the origianl Ru-Jac office, alongside archivalimages, posters, flyers, and research which tell the history of the label. He was eventually introduced to Brooks Long, who became interested in Ru-Jac Records and its history, in part because he had worked as a soul musician in Baltimore for years. Long and Coombe eventually worked together on hosting a visual presentation in Baltimore, with Coombe performing a DJ set comprised completely of Ru-Jac singles from the area.

Considering its legacy and the considerable volume of music released by Ru-Jac, its history is not very well-known. Long sees part of that as being due to the fact that it had no major successes; it may have been a springboard for Arthur Conley, but it was first and foremost a labor of love. The issues run deeper than that, however.

“Baltimore media in general is just not very good at telling its own story,” comments Long, “and a lot of the black stories of African-American history go very un-highlighted in many different ways… whatever needs to happen to awaken people to the vibrancy of Baltimore’s history just hasn’t happened.”

Marginalized communities often don’t have advocates in the public sphere to memorialize their work. If anything, there are incentives to suppress music. In the past, areas with numerous nightclubs may also be red-light districts, easily associated with crime and criminality. As cities tried to redevelop in the 1950s and 1960s, African-American neighborhoods were easy picks for city politicians for freeway construction, sports arenas, or anything else they wanted to build. Louisville once had its music scene concentrated on Walnut Street; all of its clubs were torn down in the 1960s in the name of “urban renewal.” The music and culture created by these communities falls periodically under threat.

Oral History project with Portland’s Albina Music Trust.

Cultural Awareness as Revitalization

From the moment Oregon became a state, African-Americans have been marginalized — first, by being prevented from living in the state at all, and later, by being forced to live in small, redlined neighborhoods such as Albina in North Portland. As a consequence, their art and music were marginalized as well, quite literally cut-off and isolated from the city’s mainstream musical establishments. Areas outside of that were destroyed for decades, often quite literally. The center of the city, where the Rose Quarter and Moda Center stadium are today, was previously the site of a number of jazz clubs in the city; all of them were demolished in the 1950s as part of the construction of I-5.

Founded by DJ and musician Bobby Smith, the Albina Music Trust is a project within the arts and education nonprofit World Arts Foundation, which takes an extremely close look at the legacy of the Albina neighborhood. Maintaining Albina’s history is part of the process of maintaining a neighborhood that is increasingly fragmenting under the pressure of gentrification. Part of this work has been through oral histories and interviews with local musicians, in addition to creating a documentary record.

“In a lot of these interview sessions, we’re sharing information and history together, but then connections end up being made between members of the musician community who haven’t seen each other in 20 or 30 years,” explains Smith. “That’s kind of a core value of the project — to strengthen the connection of these individuals and in the community, and to bind the narrative of these stories and histories together.”

In addition to a massive archive of digitized and previously unreleased records, Albina Music Trust have collected vintage radio programs, church sermons, basement rehearsals, and a 1977 Trailblazers anthem from when the team won the NBA championship. Physical artifacts comprise another part of their work.

“We have Albina area newspapers from the late ’60s and ’70s, advertisements for local businesses, local business brochures, videos from cultural events, home video private events, it goes on and on,” explains Smith. “We’re trying to create a picture of what life was like for musicians at that time.”

In Los Angeles, DJ Melissa Dueñas runs East Side Story, a digital archive and Instagram project that tells the story of a bootlegged music set called East Side Story, which was released between 1978 and 1983 or 1984. The music was bootlegged “oldies,” which in this context, refers to “lowrider oldies” — many of which are doowop ballads from the ’50s and ’60s. The albums came with cover art of Chicanx men and women from the community. They were so common as to be endemic throughout east Los Angeles that they eventually spread throughout the American Southwest, but the actual history behind them has been poorly chronicled. Dueñas grew up with the series, but first became interested in it because of a show she curated where the cover art was reinterpreted with LGBT people, provoking a backlash as well as a broader discussion of what these images meant, and who the people were.

To figure out who the people in the cover art were, Dueñas initially tried asking around at local record stores, but most of what she found was rumor and hearsay that tended to go nowhere. Meme culture ultimately provided the answer to the problem of anonymity: pictures bearing the title “Is this your tío?” elicited an explosive response, and Dueñas began cataloging the responses she got to try and figure out what these pictures meant to the people that were in them, and their significance in Chicanx culture.

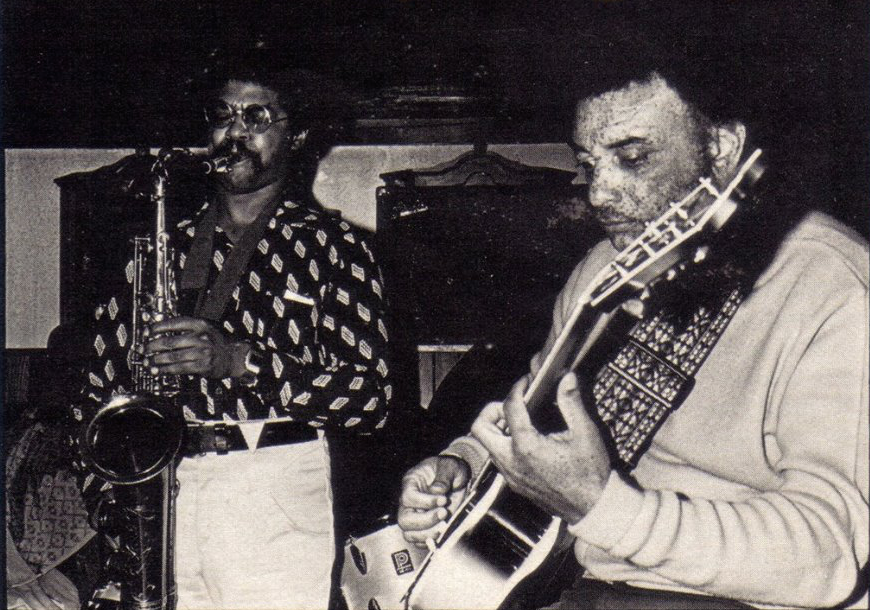

Indeed, cultural awareness can be a kind of revitalization. In Baltimore, most of the historic music joints on Pennsylvania Avenue are gone today, but one of the last survivors is Arch Social Club. Incorporated in 1912, it is one of the oldest surviving African-American social clubs in the United States — if not the oldest. It also happens to be right next to where the Baltimore Uprising began in 2015 in the wake of Freddie Gray’s death. Both the neighborhood and Arch Social Club happen to sit at an intersection of a rich cultural history, as well as a long history of institutional racism. As part of telling the story of Ru-Jac Records, Brooks Long organized a show at Arch that featured the history of Ru-Jac as well as a show by some of the label’s surviving musicians. Arch’s membership skews older and wants to ensure that the club continues as a force in the community. Encouragingly, many of the people in attendance were younger.