The camp is called Ain al-Hilweh. Early on, our narrator offers two possible translations from the Arabic: “the eye of the beautiful” or “sweet water spring”. Neither does justice to the crumbling, ramshackle concrete apartment blocks—many hand-built by refugees—bundled together on winding, close-hemmed streets. Ain al-Hilweh is home to over 70,000 Palestinian refugees and has been in existence since 1948. Its residents aren’t allowed to work in Lebanon, so jobs are few and money is scarce. Political unrest in general is high, violence not unusual, and tension exists with Lebanese security forces who not allowed inside the camp’s walls.

As a result of the oppressive atmosphere and scarcity of money inside Ain al-Hilweh, the camp is largely controlled by Fatah, the largest faction of the militant political group Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). Fatah provides young men with pocket money, and local Fatah captains with guns “mentor” younger members. In general, PLO factions clash regularly and violently with various governments seen to be antithetical to the movement to take back and reestablish a Palestinian government distinct from Israel. The Munich Olympics massacre in 1972 is the most infamous example. (Fatah is, however, is separate from and seen as somewhat less violent than Hamas, the Muslim Brotherhood affiliate organization that has governed the Gaza Strip since 2007.)

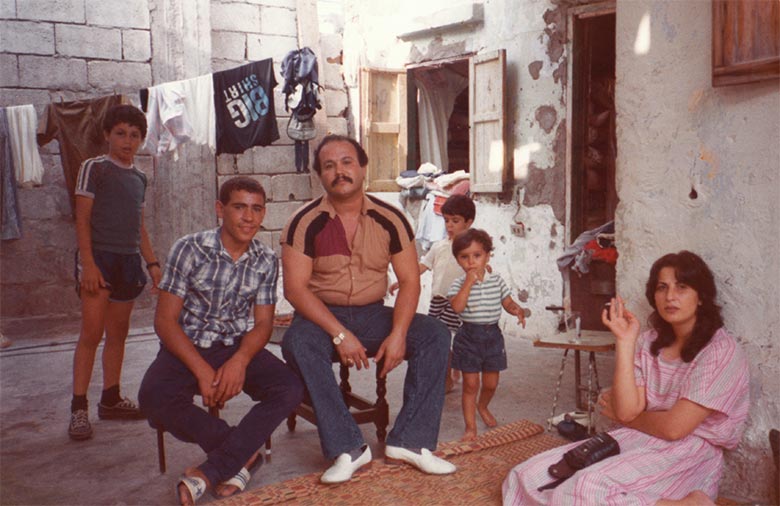

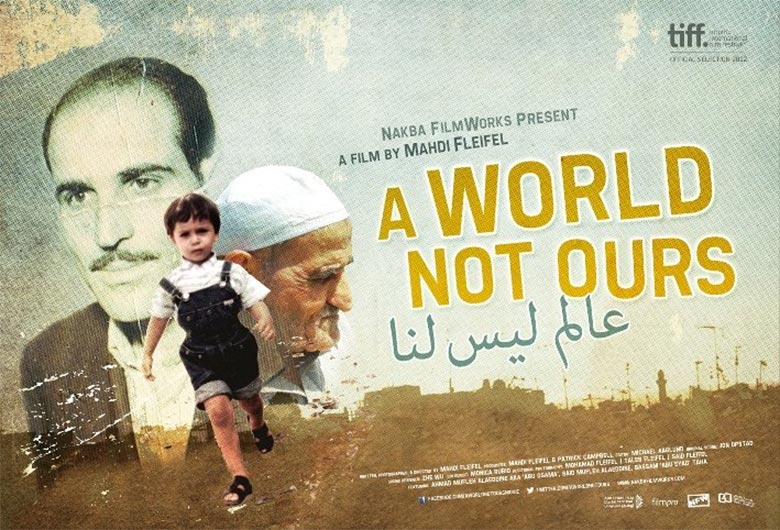

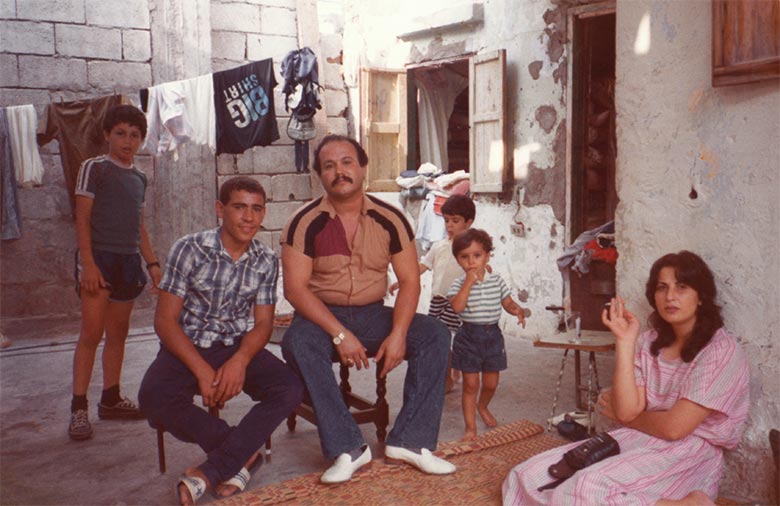

Despite this violent, stagnant atmosphere, Mahdi Fleifel, the story’s narrator, presents a much rosier perspective on Ain al-Hilweh. His memories of the “sweet water spring” are fond. Some of them come to life in grainy 1980s camcorder quality video shot by his home-movie obsessed father. Fleifel carries on the tradition; he brings his camera everywhere, and films almost everything. We get glimpses of birthday parties where children are smiling and laughing, of family reunions, and, every four years, of wildly festive gatherings to celebrate and watch the World Cup.

Having escaped Ain al-Hilweh for a better life in Dubai, and then Denmark, Fleifel and his family may come and go from the camp as they please. Fleifel returns each summer to spend time with his uncle, grandfather, and childhood friends. We get footage from many of these visits, which is interspersed with camcorded memories of more innocent days past. Recalling his childhood visits, Fleifel at one point compares trips to Ain al-Hilweh to the excitement a typical kid might have for weeklong trip to Disneyland. As the years pass, however, Fleifel notices the unrest and the emotional toll that the rose-colored glass of youth, as well as his freedom to come and go from the camp, had caused him to overlook.

Fleifel is drawn increasingly to this darker side of life in Ain al-Hilweh. The frustrations and despair of never leaving the camp, Lebanon’s work limitations, and the constant threat of violence become ever more apparent as Fleifel interviews relatives and friends. Fliefel’s lens is ultimately drawn to his troubled childhood friend, Abu Eyad, who is no stranger to violence. Fleifel recounts the time a brawl broke out after tensions boiled over at one World Cup viewing party, and which ended in at least one death. Abu Eyad was involved, though it is unclear how. Later on, after much prompting, Abu Eyad tells of being captured and tortured by electrocution as a young man for his alleged support of Yasser Arafat, founder of Fatah and former chair of the PLO. No one wants to believe Abu Eyad’s torture story. But guns are everywhere and violence common inside Ain al-Hilweh.

It soon becomes apparent that Abu Eyad can no longer take the oppressive weight of life inside the camp. Unable to leave, and unable to work for a living, he is (like many young men) in purgatory. His boredom and hatred of Lebanon, and of the politics in the region, begin to fester. Music and movies brought by Fliefel from abroad appease Abu Eyad’s moods at first. But eventually Abu Eyad becomes fed up with life in Ain al-Hilweh. “I want to blow myself up,” he confides, at one point, to Fleifel. He talks of wanting to die, simply to end a life with no prospect of betterment or change. Ostensibly in preparation, we watch Abu Eyad giving away his possessions, burning his school papers and books, and clearing out of his apartment to stay at one of the Fatah-sponsored residences.

Fleifel’s uncle Said is also increasingly on-edge. Once a cool and fun-loving mentor to Fleifel, Said is frustrated with his life as a single man. He collects cans to sell by the kilo, and cannot save up enough money to marry, despite pressure from his family to do so. Said dwells on the death of his older brother when they were teenagers (in a gun battle against Lebanese soldiers attempting to invade the camp) and tends to the pigeons he keeps on his rooftop. We learn that he once was cheated out of an opportunity to flee Lebanon by a family member, an event that darkly hovers over the fun-guy persona he portrays outwardly in the camp.

Interspersed throughout the film are little snippets of daily life. We see that inside Ain al-Hilweh, the refugees enjoy some of the privileges we all do. They drink soda and juice. Many families have a television, with daytime shows just as bad as Days of Our Lives and American Idol. Coffee and cigarettes are a daily routine. Growing up, Fleifel would watch American action movies with his uncle Said. A BMW SUV drives by in one shot. One friend of the family has a wedding, and wears a beautiful white dress, and there is dancing and a tearful celebration before the bride leaves. Clothespins hang on clotheslines in courtyards or on top of buildings.

The details of Ain al-Hilweh contrast greatly with the few images we get of a seemingly idyllic Denmark, where Fleifel spent his young adult years. While green and furtile, most days there were rainy and cold. Instead of people congregating and living their life in the narrow streets of Ain al-Hilweh, there are open but empty pastures, urban homes that sprawl, and long drives to find halal meat and other treats from home. Fleifel tells us he was embarrassed of his family while growing up in Denmark. Trying to fit in there, his father’s ways in particular were a reminder to him that he was out of place.

Fleifel is careful to include both the dark and light sides of life in Ain al-Hilweh. At times, it feels like too much footage is included – but it is diverse for a reason. The universality of these feelings, items, and activities heightens the viewer’s appreciation of both the anger and deep weariness that landlessness foments. Above all, the futility of clinging to a piece of land that is no longer one’s home comes through. Home is, after all, wherever one is, or where one continues to return. For many Palestinians, that has become Ain al-Hilweh.

Ω