While living in Arkansas, the singer Big Bill Broonzy recalled furtively reading the most famous of these newspapers, The Chicago Defender, and he made the move to Chicago in part because of what he had learned in the newspaper. Broonzy said that Black readers of the Defender were seen as brave, as it was a newspaper that promoted Black migration to the North, criticized racism in the South, and pushed for social change.1

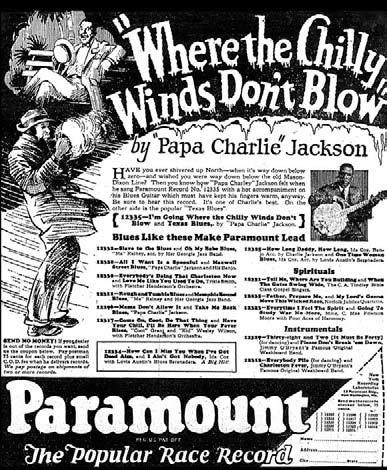

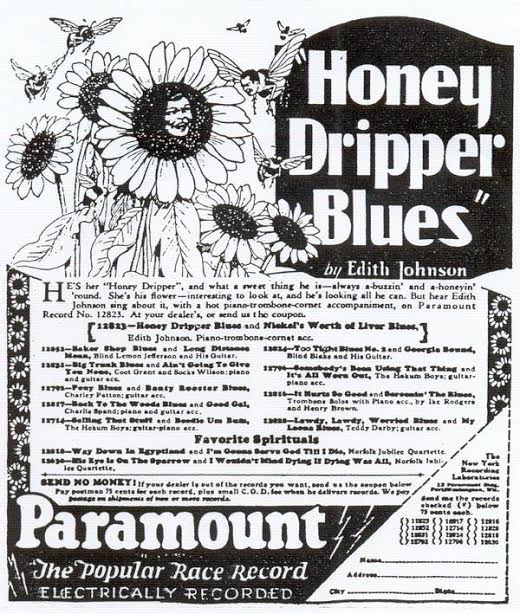

These record advertisements were critical in selling records, as they often carried coupons that could be mailed back to the companies in exchange for the music. Mark Dolan, a professor of Journalism at the University of Mississippi, writes that, “These lavishly illustrated ads told of broken love affairs, loneliness, violence and jail, in concert with travel to and from the South-by train and boat, on foot and in memory-despite the Defender‘s editorial stance urging Black southerners to leave the region.”2 It might seem strange, then, that the Defender had numerous record advertisements that nostalgized the South and referred to hard times in northern cities, a message at odds with the newspaper’s founding principles.3

These record advertisements were critical in selling records, as they often carried coupons that could be mailed back to the companies in exchange for the music. Mark Dolan, a professor of Journalism at the University of Mississippi, writes that, “These lavishly illustrated ads told of broken love affairs, loneliness, violence and jail, in concert with travel to and from the South-by train and boat, on foot and in memory-despite the Defender‘s editorial stance urging Black southerners to leave the region.”2 It might seem strange, then, that the Defender had numerous record advertisements that nostalgized the South and referred to hard times in northern cities, a message at odds with the newspaper’s founding principles.3

Recent arrivals in Chicago and elsewhere found life in the north to be alien and difficult. Audiences looking for familiar reassurances of home looked to blues music, at least in part, to mitigate the harshness of their new surroundings. These advertisements only lasted a short while before the Great Depression swept away most of the record companies, leaving only a few large companies as the survivors. Nevertheless, they offer some insight into blues music at a critical moment in its history as it adapted for a new sort of audience. Seen this way, blues music is not merely a pre-modern art form of rural people, but a highly adaptive art form that was responsive to the needs of its audience.

[audio:/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Bessie-Smith_Gulf-Coast-Blues.mp3|titles=Bessie Smith – Gulf Coast Blues]

Songs of the South

Roughly 1.6 million African-Americans left the South and moved to cities in the North during the 1920s. Chicago was one of the most popular destinations, due to its economy and the city’s reputation as an industrial city. As most of the migrants were from the rural South, they had little relevant work experience that applied to urban trades, and even those with work experience found themselves excluded from most jobs by discriminatory union practices, which left them with the lower-paying and more difficult jobs in stockyards and factories.4 New arrivals to the city tended to congregate in enclaves, such as the South Side of Chicago, partly due to discriminatory housing practices and partly due to their desire to live among other African-Americans.5 The living situations were difficult, especially for people who had perhaps never traveled outside of their home county before.

Roughly 1.6 million African-Americans left the South and moved to cities in the North during the 1920s. Chicago was one of the most popular destinations, due to its economy and the city’s reputation as an industrial city. As most of the migrants were from the rural South, they had little relevant work experience that applied to urban trades, and even those with work experience found themselves excluded from most jobs by discriminatory union practices, which left them with the lower-paying and more difficult jobs in stockyards and factories.4 New arrivals to the city tended to congregate in enclaves, such as the South Side of Chicago, partly due to discriminatory housing practices and partly due to their desire to live among other African-Americans.5 The living situations were difficult, especially for people who had perhaps never traveled outside of their home county before.

A music industry for African-Americans was created in that same year. Prior to 1920, record companies largely ignored African-American audiences, possibly out of the belief that they lacked money to spend on records — but Mamie Smith’s “Crazy Blues”, which sold over a million copies, opened the door for blues artists. These initial recordings were done with large orchestras, bands, or a piano player, and the performers were, by and large, women. These women were performers in black theater and in cabarets, and their style worked with the very primitive recording techniques of the time, which could not capture softer sounds or stringed instruments easily.

However, the comparatively high wages that these women were paid also led record companies to look elsewhere for talent. The development of the electrical recording process in 1925 made it possible for guitar-driven blues to be recorded in a clearer and more easily-heard way,6 and musicians with guitars began to travel from small towns in the South and into the urban North. The first blues guitarist to hit it big was Blind Lemon Jefferson, a Texas-born musician who was “discovered” in Dallas and brought to Chicago to perform. While there were several guitarists who recorded before Blind Lemon Jefferson, he was the first to achieve star status, and Jefferson was immediately marketed as an authentic Southern musician.

Ads for these blues records were produced to appeal to black consumers, and in preparation, record companies kept black consultants on the payroll to reproduce urban slang for the ads.7 The companies neither understood what they were selling, nor did they care as long as it sold well; distinctions between styles of blues were largely irrelevant to the executives.8 Consultants and musicians were left to shape advertising of the music and the music itself, and talent scouts such as H.C. Speir were an important part of this process. As the major record companies were all headquartered in the North and were usually isolated from the talent — Paramount Records was based in Grafton, Wisconsin for example — they relied on scouts working in major cities or the South to find new musicians. As the decade wore on, the companies were recruiting from farther afield, often using record store owners to find local talent, which set off a race for who could find more “Southern-sounding” musicians.

These advertisements are replete with visual images and imaginings of the South and the harshness of the North. The ad for Ida Cox’s “Chicago Bound Blues” is a good example, as it depicts a man leaving his girlfriend or wife to head to Chicago. This was a common plight for people living during the Great Migration as families were separated and relationships dissolved when people left. Songs were described in these ads in deliberately ambiguous ways, almost as though as the ending or story was being concealed. It was an effective hook, which spoke to familiar problems that the targeted audiences had experienced.

These advertisements are replete with visual images and imaginings of the South and the harshness of the North. The ad for Ida Cox’s “Chicago Bound Blues” is a good example, as it depicts a man leaving his girlfriend or wife to head to Chicago. This was a common plight for people living during the Great Migration as families were separated and relationships dissolved when people left. Songs were described in these ads in deliberately ambiguous ways, almost as though as the ending or story was being concealed. It was an effective hook, which spoke to familiar problems that the targeted audiences had experienced.

A number of blues songs give us insight into the nostalgic reasons that migrants looked back to the South, often using a number of loosely connected images that build to convey a singer’s feelings rather than a firm narrative. Papi Charlie Jackson references the cold of the North in “I’m Going Where The Chilly Winds Don’t Blow”, where he sings of getting off the train in Jacksonville; Blind Blake’s “Georgia Bound” begins with him mentioning he too wants to catch the southbound train and that he’s “walked out my shoes over this ice and snow.” Later, he says that, “The South is on my mind, my blues won’t go away,” and he concludes the song with images familiar to Southern listeners — of “watermelon on the vine” and wanting to “get back to that Georgia gal of mine.”

[audio:/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Blind-Blake_Georgia-Bound.mp3|titles=Blind Blake – Georgia Bound]

[audio:/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Blind-Lemon-Jefferson_Chock-House-Blues.mp3|titles=Blind Lemon Jefferson – Chock House Blues]

Of any musician, however, Blind Lemon Jefferson perhaps best embodies the desire to evoke Southern nostalgia. His first appearance in an advertisement pitched his music as “real old-fashioned blues by a real old-fashioned blues singer” and emphasized the “Southern” style of his playing. Of course, as music historian David Evans notes, Jefferson’s music was distinctive and innovative; Evans goes so far as to speculate that Jefferson’s unusual harmonics in his songs was the result of him adapting jazz techniques to blues music.9 Nevertheless, if Jefferson’s musical style was part of an ongoing and developing approach, his lyrical references to the South are commonplace, as in “Dry Southern Blues”, which begins with him saying, “My mind leads me to take a trip down south.” Even Jefferson’s songs that don’t explicitly deal with the South refer to his Texas heritage. “Chock House Blues” includes the lines “Baby, I can’t drink whiskey, but I’m a fool ‘bout my homemade wine/ Ain’t no sense in leavin’ Dallas, they makes it there all the time.”

This desire to project a Southern aura upon musicians may also have dictated the way that record labels named and labeled musicians. Mississippi John Hurt is probably the best example, in part because his name contributed to his eventual rediscovery. Okeh Records sold John Hurt as “Mississippi John Hurt,” likely because saying that he was from Mississippi was a way to tout his credentials or authenticity as a bluesman. Musicians like the Mississippi Sheiks and Henry “Ragtime Texas” Thomas got the same treatment, and so did “The Mississippi Moaner”, when somebody at the Vocalion label decided that the little-known musician Isaiah Nettles needed more spark. Geography, in this case, bestowed a certain musical pedigree.

[audio:/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Mississippi-John-Hurt_Avalon-Blues.mp3|titles=Mississippi John Hurt – Avalon Blues]

[audio:/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/The-Mississippi-Moaner_Its-Cold-In-China-Blues.mp3|titles=The Mississippi Moaner – Its Cold In China]

Concurrently, much of the same phenomenon was happening with so-called white “Hillbilly” music, which we now recognize today as country music. As railroads and textile mills were being built in the South, industrialization led to an influx of poor whites seeking work in rapidly expanding cities in the Carolinas, such as Richmond, Durham, and Charlotte. Many of these people were coming from Appalachia, one of the poorest and least developed parts of the United States.

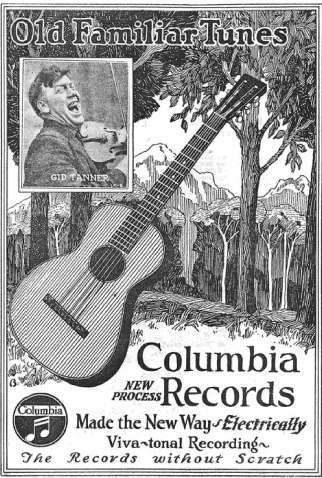

Concurrently, much of the same phenomenon was happening with so-called white “Hillbilly” music, which we now recognize today as country music. As railroads and textile mills were being built in the South, industrialization led to an influx of poor whites seeking work in rapidly expanding cities in the Carolinas, such as Richmond, Durham, and Charlotte. Many of these people were coming from Appalachia, one of the poorest and least developed parts of the United States. The migration and subsequent settlement in urban areas created a new class of consumers who were familiar with traditional music and formed a record-buying class as well as a class of musicians. Though the marketing of white country music was similar to that of blues music, as it depicted familial displacement from a traditional way of life. In an advertisement for Fiddlin’ Powers and Family, Victor notes that “Fiddlin’ Powers and his family come from the mountains of Tennessee with some records of old-time American music-songs and dances.” Likewise, Gid Tanner’s music is advertised as “Old Familiar Tunes.”

The migration and subsequent settlement in urban areas created a new class of consumers who were familiar with traditional music and formed a record-buying class as well as a class of musicians. Though the marketing of white country music was similar to that of blues music, as it depicted familial displacement from a traditional way of life. In an advertisement for Fiddlin’ Powers and Family, Victor notes that “Fiddlin’ Powers and his family come from the mountains of Tennessee with some records of old-time American music-songs and dances.” Likewise, Gid Tanner’s music is advertised as “Old Familiar Tunes.”

Lookin’ For a Home

The senses are probably the most obvious gateway to nostalgia. Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past is set in motion by the eating of a Madeleine. It’s not surprising, then, that music can trigger those same feelings of nostalgia, especially when that music is anchored to a specific time and place now lost to the listener. Academic literature on nostalgia is surprisingly sparse, but there are some articles dealing with nostalgia and immigrants that may help to explain the popularity of music about the South. Unsurprisingly, relocating from one’s familiar environment is deeply disruptive, often to the point that people suffer depression and disassociation.

In an article written about Russian immigrants in San Francisco after the fall of the Soviet Union, Alexander Zinchenko notes, “Our sense of self-constancy is supported by the language we speak; cultural myths, values, and rituals shared with others; identification with certain social groups; and habitual lifestyle and everyday routines.”10 While not all of the above is true for African-Americans migrating to the North in the 1920s, some of the concepts may be useful in explaining the popularity of blues music at that point in time.

In the words of Zinchenko, “The familiar transitional space of home ensures not only orientation in the world but also knowing oneself within the world and a sense of control over one’s ego.”11 Immigration removes the immigrant from a familiar space, creating dissonance between experience and memory;12 hence, the disruption in many people’s lives contributed to feelings of alienation and numbness. Zinchenko concludes that one of the most effective ways to combat this feeling of isolation is spending time within an “immigrant enclave”, where familiar customs and mores mitigate feelings of alienation.

[audio:/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/The-Skillet-Lickers_Alabama-Jubilee.mp3|titles=The Skillet Lickers – Alabama Jubilee]

For a long time, contemporary white musicologists and folklorists insisted on viewing blues music as a form of music that was pre-modern and “old timey.”13 White audiences began to come around to country blues music by the end of the 1930s, after the genre had been surpassed by new forms of blues music. John Hammond, a record promoter and civil rights advocate in New York, hosted an influential concert series in 1938 and 1939 called “From Spirituals to Swing.” Designed as a showcase of all forms of African-American music, from gospel to blues to jazz and hosted for a racially integrated audience, the concerts were groundbreaking for their time. Initially, Hammond wanted Robert Johnson, but after discovering that Johnson had died, Hammond decided Big Bill Broonzy would be the best fit. However, white audiences had their own notions of what an “authentic” bluesman would look like, and Hammond had Broonzy appear in the costume of a sharecropper — despite the fact Broonzy had lived in Chicago for years and was, by the standards of the day, very successful.14

For a long time, contemporary white musicologists and folklorists insisted on viewing blues music as a form of music that was pre-modern and “old timey.”13 White audiences began to come around to country blues music by the end of the 1930s, after the genre had been surpassed by new forms of blues music. John Hammond, a record promoter and civil rights advocate in New York, hosted an influential concert series in 1938 and 1939 called “From Spirituals to Swing.” Designed as a showcase of all forms of African-American music, from gospel to blues to jazz and hosted for a racially integrated audience, the concerts were groundbreaking for their time. Initially, Hammond wanted Robert Johnson, but after discovering that Johnson had died, Hammond decided Big Bill Broonzy would be the best fit. However, white audiences had their own notions of what an “authentic” bluesman would look like, and Hammond had Broonzy appear in the costume of a sharecropper — despite the fact Broonzy had lived in Chicago for years and was, by the standards of the day, very successful.14

The white fascination with the “primitive” in music was sparked by prominent folklorists like Alan and John Lomax, who wanted to find musicians untainted by contact with popular culture. The Lomaxes were genuinely interested in preserving undocumented folk culture, and their work helped in part to spark an interest in “authentic” African-American culture that was untouched by popular culture. Blues music, along with country music, was a place for white Americans to criticize and escape from expressions of popular culture, contrasting the supposedly “authentic” blues music with commercial or corporate music. Yet this view was simplistic and ignored the complicated origins of this music, and we as listeners cannot understand the music if we don’t understand the context in which it was created.

Even as blues music changed substantially, its nostalgic impulses never really disappeared. The popularity of “I Feel Like Going Home” by Muddy Waters and “Going Back Home” by Howlin’ Wolf are records of a time when blues went electric; though the musical world changed substantially, the songs show that nostalgia in the blues hadn’t really diminished at all.

University of Mississippi journalist Mark Dolan recently noted that one of the most common license plates he sees in Mississippi are those from Illinois, as people still drive down to see family members in the South. Even after the passage of ninety years, understanding the role and prevalence of nostalgia in blues music is important to understanding how it was created, why it was created and the history of African-Americans in the twentieth century.

[audio:/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Muddy-Waters_I-Feel-Like-Going-Home.mp3|titles=Muddy Waters – I Feel Like Going Home]

[audio:/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Henry-Thomas_Arkansas.mp3|titles=Henry Thomas – Arkansas]

References

1 Roger House, Blue Smoke: The Recorded Journey of Big Bill Broonzy, Baton Rouge, Louisiana: LSU Press, 2010, 50.

2 Mark Dolan, “Extra! Chicago Defender Race Records Ads Show South From Afar!” Southern Cultures, Volume 13, Number 3, Fall 2007, p. 106.

3 Mark Dolan, “Extra! Chicago Defender Race Records Ads Show South From Afar!” Southern Cultures, Volume 13, Number 3, Fall 2007, p. 106.

4 James Grossman, Land of Hope: Chicago, Black Southerners, and the Great Migration, Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press, 1989, 182-183.

5 James Grossman, Land of Hope: Chicago, Black Southerners, and the Great Migration, Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press, 1989, 127.

6 David Evans, “Musical Innovations in the Music of Blind Lemon Jefferson,” Black Music Research Journal, Volume 20, Number 1, (Spring 2000), p. 84.

7 Mark Dolan, “Extra! Chicago Defender Race Records Ads Show South From Afar!” Southern Cultures, Volume 13, Number 3, Fall 2007, p. 106.

8 Interview with H.C. Speir, February 8, 1970. http://www.tdblues.com/2010/08/gayle-dean-wardlow-research-interviews/

9 David Evans, “Musical Innovations in the Music of Blind Lemon Jefferson,” Black Music Research Journal, Volume 20, Number 1, (Spring 2000), p. 96.

10 Alexander V. Zinchenko, “Nostalgia: Dialogue Between Memory and Knowing,” Journal of Russian and East European Psychology, Volume 49, No. 3, May-June 2011, 87.

11 Alexander V. Zinchenko, “Nostalgia: Dialogue Between Memory and Knowing,” Journal of Russian and East European Psychology, Volume 49, No. 3, May-June 2011, 90.

12 Alexander V. Zinchenko, “Nostalgia: Dialogue Between Memory and Knowing,” Journal of Russian and East European Psychology, Volume 49, No. 3, May-June 2011, 89.

13 Richard Middleton, “O Brother, Let’s Go Down Home: Loss, Nostalgia and the Blues,” Popular Music, Volume 26, NO. 1, 52.

14 Roger House, Blue Smoke: The Recorded Journey of Big Bill Broonzy, Baton Rouge, Louisiana: LSU Press, 2010, 50.

[…] blues singer, Mamie Smith, hit big in the 1920s with her million dollar record, <a href=”http://www.redefinemag.com/2014/blues-music-marketing-nostalgia-using-race-records/”>“Cra… Blues.”</a> Smith and other “Southern sounding” musicians, such as Blind Lemon […]