Tape reviewed at MIPoPS featuring the marquee of The Lusty Lady, which reads, “The Nude World Order.” (Credit: Jill Freidberg)

Independent Media Center Archives: The 1999 World Trade Organization Protests

When delegates of the World Trade Organization (WTO), established in 1995 to promote free trade, convened in Seattle in the fall of 1999, they were greeted by tens of thousands of protesters. These activists argued that trade agreements forced countries to abandon labor and environmental protections for the sake of corporate wealth.

Jill Freidberg, a documentarian and professor who studied anthropology and environmental science at the University of Oregon, recalls what drove her to attend. She describes herself as “an Earth First-er in college. I had done the whole direct-action thing and gotten super burned out and pessimistic. And everybody’s like, ‘The WTO protests are gonna be the turning point.’ I was like, ‘Maybe.'”

Though unsure of the protests’ impact, Freidberg focused single-mindedly on their documentation, and founded the Independent Media Center (IMC or IndyMedia) in a downtown building in November 1999. Alternative video collectives from around the country, including the New York-based Big Noise Films and Paper Tiger TV, brought their tapes for uplink to IMC’s website. Using primitive email, flyers, and word of mouth, IMC also urged independent videographers to submit their tapes.

“Once people found out about the IMC space, hundreds and hundreds of people went through the door,” recalls Freidberg. Meanwhile, she and others copied these 400 hours of footage onto Betacam, considered the most stable and high-quality video format.

IMC’s ambitious project, which harnessed the power of the nascent internet, presaged on-the-ground social media coverage of the Arab Spring, Black Lives Matter, and 2019 Hong Kong protests by two decades.

“[The IMC] was the first self-publishing platform on the internet. The idea that people could publish their own news was a big idea,” Freidberg explains.

Using the 400 hours of footage collected by the IMC, Freidberg created This Is What Democracy Looks Like (2000), a visceral portrait of a kaleidoscopic array of anti-WTO protesters, from grandmas to Teamsters, all wielding creative props, posters, and costumes. She also became the guardian of those tapes, which lived under her stairs. Around six years after the protests, Freidberg tried to get UW to take them, but there were no funds for digitizing magnetic media at the time. Then, in 2018, Freidberg reached out to UW again. With the help of MIPoPS, she was finally able to preserve the tapes.

This Is What Democracy Looks Like repeatedly juxtaposes this citizen journalism with more mainstream coverage, exposing blind spots and fearmongering. On local news, a police officer says only twenty people were harmed, while cameras reveal crowds being dragged, tear-gassed, and hit with batons. Videographers were energized to preserve media coverage they perceived as biased. According to Freidberg, one man who was housebound for health reasons nonetheless contributed to the archive by recording a week’s worth of news coverage onto VHS. These efforts were especially valuable given that news stations frequently threw away their tapes.

Freidberg characterizes the mainstream coverage as “infantilizing and just diminishing the people who had come to Seattle to protest.”

“[The media called the protestors] a rag-tag bunch of disorganized hippies [and] hypocrites, because they were wearing jeans made in a sweatshop or whatever,” she reflects, ” — [when they were actually] 80,000-plus people ranging from farmers from Oklahoma to steel workers from Spokane. So that was frustrating. The commercial media was really exploiting any evidence of those divisions.”

Hannah Palin, of MIPoPS and formerly University of Washington’s Special Collections, driving all the WTO tapes from Jill Freidberg’s house to UW Special Collections. (Credit: Jill Freidberg)

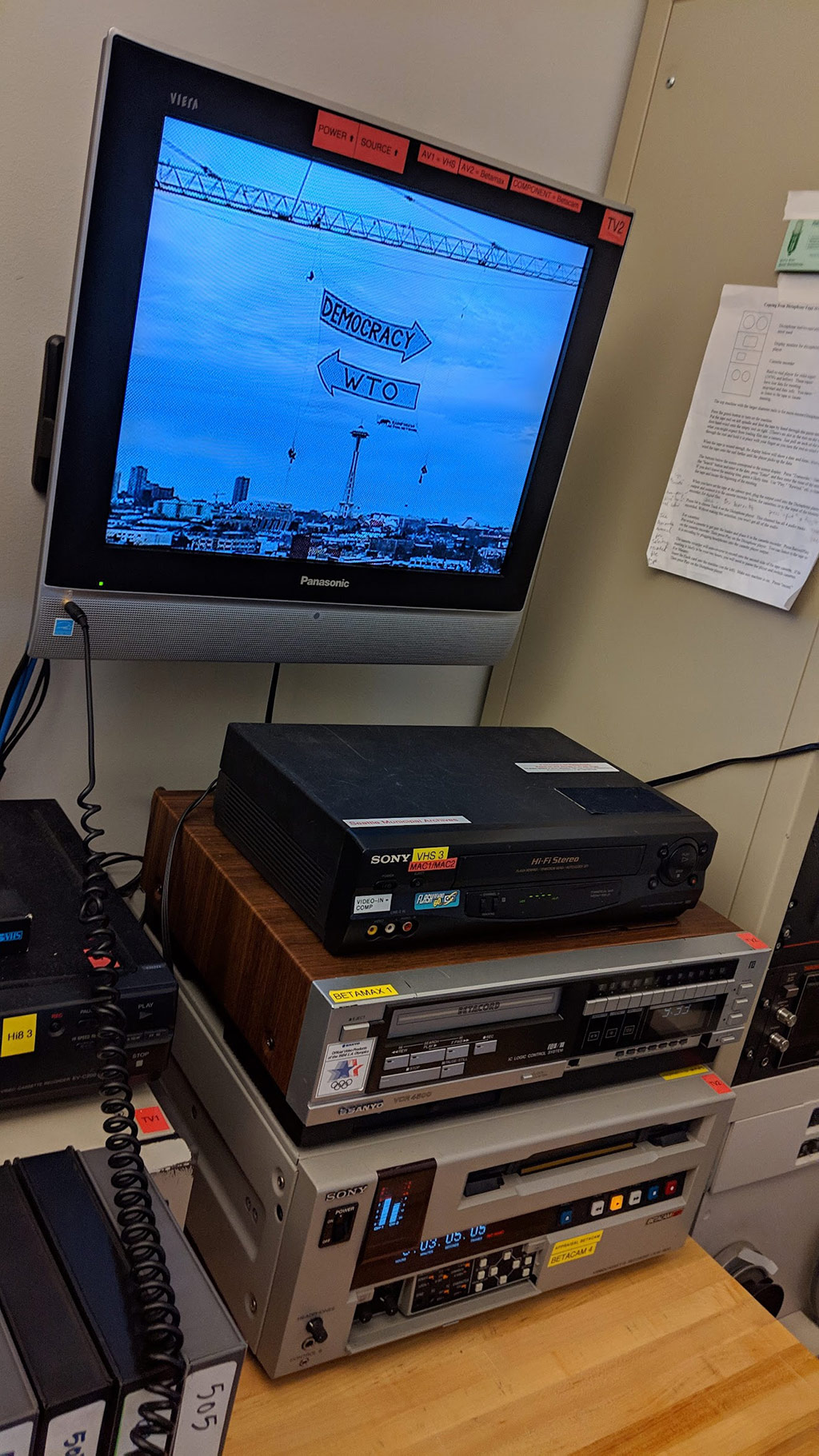

A tape being reviewed at MIPoPS, which shows banners that read “Democracy” and “WTO,” flying over Seattle. (Credit: Jill Freidberg)

In contrast, says Freidberg, “The people’s coverage was so much more comprehensive. I’m still going through and seeing stuff that I’ve never seen before, and realizing that there are intersections where there really were three different cameras at three different angles for the whole day. The entire day unfolds from dawn to dusk through three different people’s cameras who didn’t even know each other. It’s fascinating to piece together.”

Those 400 hours include not only marches and rallies, but also teach-ins and spoken-word open-mics. Freidberg highlights Jourdan Imani Keith, who would go on to become The City of Seattle’s 2019-2021 Civic Poet, and hip-hop artist and future KEXP DJ Gabriel Teodros. Public artist DK Pan led a Kabuki-style funeral march from Pioneer Square to Westlake, complete with a coffin, ringing bells, and fake blood. In her book of essays The Witches Are Coming, author and screenwriter Lindy West recalls joining in on the protests as a high-schooler, even though she wasn’t totally sure what they were about. All the while, the Infernal Noise Brigade — an anarchist marching band with matching gas masks — contributed to the pulsing soundtrack of the protests.

“They were like Where’s Waldo?; they just kept popping up,” laughs Freidberg.

As evidenced by the dancing and mosh-pit atmosphere, “People were clearly really drawn to this street party aspect of the protests,” she says. “That was the first time for a lot of people to experience that special feeling of freedom where you’re like, ‘We have literally taken the streets.'”

(Left to Right:) David Solnit, Dana Schuerholz, and Jill Freidberg on November 30, 2019, trying to get a projector to work, so that they could project rescued footage from the WTO protests onto the Convention Center. (Credit: Jill Freidberg)

The WTO protests were not only the first glimmer of social consciousness for many, but also a template for future protests. As Freidberg points out, they popularized a “repeat after me” style of rallies later used by Occupy Wall Street. Outside of the U.S., they “register[ed] for the rest of the world — that, of course, was much farther ahead in terms of understanding and resisting corporate globalization — that the US was not completely asleep. Even in the belly of the beast people were waking up.”

Happily for historians and curious Seattleites alike, MIPoPS has successfully digitized all 400 hours of footage, which will become available to the public online through UW Special Collections. Freidberg has kept busy with metadata work — tagging videos by topic, person, and location. It’s a tricky task given how much Seattle has changed in the past two decades. Equally arduous has been tracking down every videographer and attaining their permission to post their footage online.

“I should have been a PI, because there are people I found who I shouldn’t have been able to find,” jokes Freidberg.

The possible uses for the footage are vast. As Freidberg reflects, “I think it would be really cool if a group of library science graduate students and geographers wanted to create a digital map or reality.”

JUMP TO: ARTICLE CONTENTS